FRANKENSTEIN by Mary Shelley

On the letters I-III and IV sent to Margaret Walton from her brother Robert Walton

On the key difference between letters I-III and letter IV at the beginning of Frankenstein

Letters I-III at the beginning of Frankenstein written by the explorer Robert Walton to his sister Margaret are all composed with a tone of excitement, joviality and reflection. Reading them it is evident that the character is alive with the anticipation of exploration, the discoveries he hopes to make and the friendships he seeks. In the narrative where he explores his feelings of loneliness, the timbre is not excessively depressive. Rather, he writes with command over his emotions, and the reader does not feel he is desperate. As such, the rhythm is measured and of the uniform steady structure one might expect a letter to have; phrases are spacious and balanced.

Whereas, throughout letter IV the tone is frantic and agitated; Walton narrates with a sense of urgency, and the reader is given a sense that the relative halcyon of Walton’s psychological state in letters I-III is no more. The previous composure is replaced by drama and panic. This is due to the fact that Walton is narrating the events that have most recently occurred such as the appearance of Victor Frankenstein and his sighting of the mysterious creature on the ice. Therefore, the speedy and tensioned nature of the letter is because of the vehemence of the narrator’s emotions. In contrast with the steady rhythm of letters I-III, letter IV is accelerated – turbo-charged – making the sentences fractured and dissonant. The staccato dynamic effect this produces emphasizes the animation of Walton as a result of the strangeness of the things that have happened.

On how Robert Walton describes Frankenstein in the letter. Is it believable?

Walton describes Victor with awe and fascination. He conveys him as a man ‘of gentleness and loftiness of spirit’ and notes that despite his physical appearance, he deems him to be a very intelligent man whose character is measured and refined. Walton is able to identify a number of Victor’s features, helping him to better understand and make conjectures as to the true nature of his character. Phrases such as ‘his eyes that have generally an expression of wildness and even madness’ and ‘voice whose varied intonations are soul-subduing music’ convey Walton’s attraction to Victor Frankenstein’s character, suggesting he has an alluring presence. Walton marks that whilst many elements of Victor Frankenstein’s character are articulate and express sensitivity, he is nevertheless clearly agonized and deeply troubled by something. The direness of Victor’s physical state is shocking, making the reader feel the same reverence as Walton does toward Victor; a character enveloped by pre-eminence.

I think Walton’s depiction of Victor Frankenstein is somewhat exaggerated and romanticized (from a literal perspective); having just met Victor he is able to convey the intricacies of his emotions and the truths behind his disposition. The narration seems somewhat improbable in terms of the extent to which Walton understands and captures Victor’s psyche. The idealized nature of the description reinforces this and makes the letter read less like the account of an unbiased narrator as opposed to a narrator who knows and sees all. However, when considered as a narrative which seeks to fulfil a literary motive, one which is gothic and altogether dystopian, a reader can appreciate the fact that the wonder Walton expresses at Victor is something which ensures the forthcoming narrative is going to be vehement and severe, full of tragedy. It is evident that Shelley has chosen to introduce Victor’s character through Walton’s eyes because she knows it will serve to intensify the spectacle of the story he is about to tell. So, provided the reader shows a certain amount of discretion, it is believable within the structure of a romantic novel, full of ardour.

On why Robert Walton chooses to tell Victor Frankenstein his story

It is the case that Victor sees Walton as a reflection of his younger self. He sees that Walton has a zealous and ambitious nature which is focused upon the attainment of glory through exploration; just as Victor was intent upon attaining glory through science. As a result, Victor wishes to narrate his story to Walton in order to prevent him from making the same mistakes he did. Also, remember that Victor Frankenstein and Walton are both characters who suffer deeply because of a lack of human connection. In Walton Victor finds someone who is willing to listen and sympathize with him; thus, he is able to unburdening himself of the suffering and guilt he feels. Moreover, Victor realises that he cannot wind back the clock, he cannot reverse what he has done. But he can offer cautionary advice to others who might be on the same path as him; warn them against the danger of unchecked aspiration and ego. Walton is one of these people whom he feels he has a moral obligation to help. Furthermore, Victor no longer has control over much of anything anymore. All he has left to control is that which he tells others about himself, his story, his life’s narrative is something he can influence. Whilst he remains alive, he can still put forward his version of events and be remembered on his own terms, to a certain extent.

*’Talking It Over’ by Enoch Wood Perry Jr., 1872 AD

On what effect the environment has on Robert Walton and Victor Frankenstein’s relationship

When Victor Frankenstein decides he will tell Robert Walton his story, the reader assumes the desolate and altogether remote nature of the environment they both occupy contributes toward his final decision. Such an environment likely makes Victor feel that there is sufficient space and freedom to narrate his tale; a feeling of closeness and intimacy between the two men because they are physically isolated. There is little chance of disturbance or interference. Moreover, because Walton has for the moment come to a halt in the course of his journey, he has the time and freedom to hear Victor out. Victor too has come to something of a standstill, grief-stricken, lonely and out of civilisation’s way.

Once again, it comes back to everything the two men have in common. The situation and space they both find themselves is further evidence of this and serves as a catalyst for expression and deep, vehement reflection. The arctic environment is powerfully symbolic within the context of the story. It is a place of mesmeric and captivating natural beauty but also trepidation, danger and unpredictability. Walton has sought this environment out; Victor’s fate encapsulates these realities; his desire to go beyond the apparent limitations of nature in his quest to achieve something of unrivalled profundity. Therefore, Shelley’s decision to have his tale of devastation narrated against the backdrop of one of the harshest and most unforgiving climates nature has to offer is symbolically potent, it is manifest of Victor’s destiny. As such, the environment Shelley chooses to depict makes the story more believable and naturally occurring.

On how Victor Frankenstein initially responds to his monster

Throughout this section, Victor Frankenstein’s feelings toward the monster are very negative. Phrases such as ‘the miserable monster whom I had created’ and ‘the approach of the demoniacal corpse to which I had so miserably given life’ emphasize Victor’s immediate alienation toward the monster and the way in which he feels he has wronged. He refers to the monster in terms that do not depict it as in any way human. The phrase ‘and his eyes, if eyes they may be called’ inform the reader that Victor has a vehement sense that his creation is not what he intended it to be, he judges it to be loathsome and detestable entirely based upon his initial reaction to its appearance.

*Boris Karloff as ‘Frankenstein’ in ‘Frankenstein’ (1938)

Furthermore, Victor misjudges his creation’s initial responses to the world (his expressions and movements) as sinister. Phrases such as ‘his jaws opened’ and ‘a grin wrinkled his cheeks’ followed by ‘Oh! no mortal could behold the horror of that countenance’ evidence this. He does not consider these actions to be in any way innocent, like those of a newborn. The shock he feels very quickly manifests itself as hatred and loathing. The reader, not being in Victor’s position, can appreciate that these motions and expressions can and should be interpreted sincerely and that a creator should realise the intricate complexity of the situation he has brought about, and act with prudence and sagacity accordingly.

In addition to this, as the novel moves forward, the reader is provided with the perspectives of other characters and their responses to the monster. Perhaps expectedly, they react in a similar way to Victor, with shock and horror. However, they encounter the monster under very different circumstances. For example, William, the boy murdered by the monster, was understandably completely terrified by it; in the woods whilst he was alone and lost. The De Lacey family were in a comparable situation and responded in a similar fashion as William. However, Victor Frankenstein, as its creator, should’ve acted with a greater degree of diligence.

A creator should act with more assiduity and think with the same rigour and attentiveness displayed during the process of the creature’s assembly, after it. It was as a result of Victor’s obtuse behaviour that the monster developed in the way it did and became emotionally perverted and murderous. These fledgling moments of the monster’s existence are perhaps the most important in the whole process and should be regarded as such. Victor did not have a plan, and he was caught unawares, an error that dictates the course of the entire book going forward.

Victor is very ignorant in this sense and may be seen as even more so as the book progresses. This is because he does not at any point acknowledge the deficiencies in his scientific process nor welcome the opportunity to learn from them. Instead, throughout the extract all he considers is the ‘bitterness of disappointment’, remarkably selfish behaviour given the potential severity of the consequences of his actions. As such, he does not realise in any way at this stage that he has a duty toward his creation, that he has a responsibility to nurture it as best he can and make its existence a happy one. He does rightly accept personal responsibility for its creation, but he does not act upon these feelings, a failure that haunts him for the rest of his life.

It must be acknowledged that these are impressions that are not fully developed by the reader until later stages in the novel. Nevertheless, the extract is crucial evidence for these impressions and should be considered an extremely important stage in the novel when exploring the way in which Victor Frankenstein behaved toward his creation.

On who the monster killed and for what reasons

*’The Murder’ by Paul Cezanne, 1870 AD

- William Frankenstein is the youngest brother of Victor Frankenstein. Following the Creature’s repeated rejection, he feels tremendous loathing for all humanity, Victor in particular. Therefore, when he encounters William, realising he is Victor’s brother, he seizes upon the opportunity to deal his creator an emotional blow, seeking retribution for the wrong he has done him. In a culmination of these feelings of rage, the Creature strangles William to death.

- Justine Moritz is a loyal servant of the Frankenstein family. Whilst the Creature does not physically murder her, he is nevertheless responsible for her death. He frames Justine for the murder of William; planting a locket which was on William’s person on Justine. Following this, a trial ensues, and Justine is found guilty of the crime based upon the evidence. The Creature brings about her death to further Victor Frankenstein’s emotional anguish and guilt and in order to vent his anger and hatred for all humankind.

- Henry Clerval is the best friend Victor Frankenstein had. The Creature strangles Clerval after Victor decimates the components of the female companion he promised the Creature. The murder is an act of reprisal against Victor for breaking his promise.

- Elizabeth Lavenza becomes Victor Frankenstein’s fiancée. The Creature makes good upon the threat he issued Victor during their previous encounter; ‘I shall be with you on your wedding night’. The murder is portrayed as Victor’s punishment for having denied the Creature companionship.

- Victor Frankenstein is the novel’s main protagonist and the most debateable inclusion in this list. Victor dies as a result of his pursuit of the Creature through the arctic. His death is not at the hands of the Creature directly, but it must be acknowledged that the obsessive manner in which Victor pursued the Creature brought about his demise.

On whether Shelley created a tragic hero in both Victor and the Monster

Throughout the novel, Victor Frankenstein is depicted as a brilliant scientific mind; one willing to sacrifice everything in pursuit of a single goal. In this sense, he is a monomaniac and a successful one at that. He does achieve his goal of creating life, however unsuccessful he may have proved in his other central ambitions of defeating death and improving humanity. Nevertheless, particularly at the novel’s outset, the reader is made to view Victor as an inspired and ingenious creator who achieves something wholly unprecedented.

Victor’s downfall is because of the flaws in both his character and his scientific process; his arrogance, conceit and general lack of planning are all detrimental to the achievement of these other goals.

Moreover, like all heroes, he suffers greatly. He feels the darkest and deepest human emotions of remorse and iniquity. Victor acknowledges that which he has done wrong but at too late a stage to do anything about it. Heroes tend to act upon their instincts and realizations in a timely fashion, something that Victor Frankenstein failed to do. And these personal failures were responsible for the deaths of those closest to him. Heroes are generally heroes because they succeed in the prevention of death, not because they cause it.

*’Morpheus’ by Jean-Bernard Restout, 1771 AD

Finally, Victor’s death occurs during his pursuit of the Creature, an act which on the face of it might seem heroic were it not for the fact that the same emotions which drove him before, continue to fuel his Romantic hopes for vindication; which he believes might be attained by the capture of his Creature. The reader is made to feel concern and a degree of sympathy for Victor, not for the first time in the novel and for altogether similar reasons. Therefore, I think the amount of wrong done by Victor outweighs the amount of right he does throughout the novel. It cannot be denied that the ‘tragic’ elements of a ‘hero’ are all there, just without enough fortune to balance the scales. In addition to this, I do not think his character completely fits the conventional mould of a ‘classical hero’ nor any other ‘hero’ for that matter.

The Monster on the other hand is a figure who originally, at the beginning of his life had great promise and who had all of the mental characteristics needed to succeed and be a good person. At various points in the novel, he showed traits of compassion, morality and righteousness. His devastation was really no fault of his own and did not stem from arrogance or other flaws in his character. Rather, the vicissitude he experienced was because of repeated spurning and dismissal despite his good intentions, enough to result in feelings of hatred in the best of us. The Creature’s constant denial of any sense of acceptance and connection made him feel unparalleled degrees of self-loathing and hatred.

Perhaps the most tragic element of his story is his ravaging of the people who were most capable of understanding him. As such, his story concludes similar to how a ‘tragic hero’[es] might; with a great deal of understanding and cognizance of the world coupled with melancholy and dejection.

Therefore, it could be said that the Creature’s development went full circle; inherent virtue and morality followed by corruption due to neglect, finally ending with wisdom attained through experience together with a more mature sense of understanding. So, like all worthy heroes, his innocence was corrupted by malign oppressors, he did wrong as a result but still managed to preserve a sense of emotional sensitivity and thoughtfulness in the end.

In terms of nobility and heroism, I vote for the Creature over Victor Frankenstein. Both of their stories were certainly very ‘tragic’; however, I believe the sum total of the sin committed by both is enough to rule them out of the ‘hero’ category.

On the role of women in ‘Frankenstein’

Who are the women?

- Caroline Beaufort Frankenstein:

Caroline is Victor Frankenstein’s mother. Throughout the novel she is depicted as someone who passionately cares for her family. She married Alphonse Frankenstein (Victor’s father) following her own father’s death. Later, she adopts Elizabeth who falls ill with scarlet fever; Caroline contracts the disease from her and later dies as a result.

- Elizabeth Lavenza:

We are first introduced to her as Victor Frankenstein’s adopted cousin. She later becomes his fiancée at Alphonse Frankenstein’s request. She is murdered by Victor Frankenstein’s Creature on her wedding night.

- Justine Moritz:

Justine is the Frankenstein family’s beloved servant who is treated as a member of the Frankenstein family. In the novel she is executed following her being wrongly convicted of William’s murder.

- Safie

Safie, a character also referred to as simply ‘the Arabian’, is the daughter of a Turkish merchant (who sought to control her) and the lover of Felix De Lacey; a member of the family the Creature stalks and learns from following his escape. The reader is told that Safie left her father to be with Felix who teaches her a variety of subjects in lessons that the Creature listens in on.

- Margaret Saville

Is the sister of Robert Walton. At the beginning of the novel, Walton writes a number of letters to Margaret detailing the events which occurred up to and including his encounter with Victor Frankenstein.

*’Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy’ by Artemisia Gentileschi, 1606 AD

What is their role?

Throughout ‘Frankenstein’, women are portrayed as being secondary figures to the men who, for the most part, dominate the narrative. Despite the significant ways in which they serve the male characters, they do not have as great an influence on the novel’s most central events. All of the women are compassionate and virtuous, but the narrative condemns them to a domestic existence in which they are done wrong by those they care for so deeply.

This is evidenced by the fact that the novel’s three narrators are male; instead of having their own voices, the female characters are spoken for and to. All are victims of injustice, perpetrated by the male characters who suffer and portray their female relatives as catalysts for their anguish. In this way their roles are undermined, their significance downplayed and minimized. There is very little in the novel which strays from this theme of subjugation. Safie is the only female character who is depicted as unwilling to be administered and who wishes to maintain independence from the male who seeks to maintain control of her. However, the novel does not give her the freedom to narrate her personal experience. Rather, it is told by the Creature in his narration.

As such, their oppression and persecution emphasize the many ways in which Victor’s life has gone astray; the most severe aspect of which is his ideological change; from one with a sense of fellow feeling and sensitivity at the beginning of the novel to one obsessed by the relentless pursuit of an objective, which leads to his unwinding. The lack of female presence and perspective in the novel creates an imbalance, one which mirrors the imbalance in Victor’s life.

Therefore, put simply, ‘Frankenstein’ highlights that societal spoliation is enacted very readily and ambitiously by man when there is an absence of female perspective and influence to balance and counter it.

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR by William Shakespeare

A note on the play and its relationship to history

It is very important to remember when reading the pieces below that they are all about and relevant to Julius Caesar the play and not necessarily the events which occurred historically relating to Caesar. Whilst there are many aspects of Shakespeare’s play which align with history, there are also certain elements which do not, such as certain character portrayals and the sequencing of events. I of course encourage the reader to draw parallels between the pieces in this section and those in my classical civilisation section which relate to this period of Roman history, but I would caution to be mindful and to remember the disparity that exists between history and fictional works based upon it.

On the uses of fate and finality in Julius Caesar

Do we feel sorry for Brutus? You could say that Brutus brought all of his sorrow and grief upon himself. Or that it was not all his fault, and he could not know what Marc Antony would do. Shakespeare portrays Brutus as foolish and unable to see what is happening. If we look back at the circumstances with which Brutus entered the play, we may see more clearly. Cassius knows that Brutus is a close friend of Caesar’s and that it would be beneficial to have him on board the conspiracy. So slowly, gradually, gently he tries to convince Brutus that Caesar is a tyrant whose ambition will be the demise of Rome. Brutus at first is not convinced but soon begins to be troubled and disturbed by what Cassius has said. He cannot sleep over it and is tormented by the thoughts he is having. It is true that Brutus may have been having these thoughts before Cassius spoke of them, but whether he would have acted upon them without Cassius’ persuasion is unknown. Cassius’ technique of persuasion is attempting to mirror the thoughts that he believes Brutus is having, to remind Brutus of them. Brutus admits that he is having thoughts but does not reveal what they are. Cassius sees this as a chance to truly convince Brutus of Caesar’s evils. Brutus realises that Cassius may be up to something and is wary. Cassius ends up convincing Brutus and the rest is history. So, was Cassius wrong to brainwash Brutus or should Brutus have been stronger and withheld Cassius’ tongue. Was it Cassius’ ‘’fault’’ that what happened, happened?

*’The Death of Julius Caesar’ by Vincenzo Camuccini, 1806 AD

Was murder justified by their cause? Would there have been any other way? What would Caesar have done? Did he deserved to be killed? Perhaps in this case murder was justified. There are many what ifs in Julius Caesar. Many crucial questions that are answered by your moral stance. All of these questions and thoughts of morality build up to a sense of finality and fate. There is no denying that Brutus was stupid and arrogant with his choices. Almost a comedic set of circumstances. A Comedy of Errors? Was the greatest mistake murdering Caesar? Or was it allowing Marc Antony to speak and stir the Roman people up into a rage? Was Brutus’ fate already written when he plunged the dagger into Caesar’s body? If you think how many times Cassius attempted to put Brutus straight and remind him of the consequences of his actions is this is to be pitied. So, when all hope is gone and Brutus is sat in his tent, feeling sorry for himself and wishing Portia was still alive it feels as if the end is coming, and Brutus’ time is up. This is his fate. Before they go to war, Brutus and Cassius argue, blaming each other for their grief and misfortune. Cassius said that Brutus wronged him, Brutus said that Cassius wronged himself, and this is a continuing theme throughout the argument.

This is the end of the conspiracy and realising that they have been defeated, Brutus and Cassius slay themselves. Ironic that. SLAY themselves. Isn’t it funny that the blade they had for Caesar they had for themselves. Brutus said that if the people so wished he had the same blade for himself. Turns out they did, and he did too.

Can we help but feel sorry for Brutus? Can we help but feel sorry for anyone in his position. Perhaps only those with harsh hearts wouldn’t. Those who do not pity the helpless, those who have wronged, weeping and crying for help and mercy. Turns out that there was nobody to pity poor Brutus and Cassius. What a heartless world we live in!….. Previous work. 2022-23

What is a tragedy?

A tragedy is a play in which tragic events occur.

How does the ‘Tragedy of Julius Caesar’ compare to others by Shakespeare?

When comparing ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’ to others, such as ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’, perhaps the greatest and most prominent difference is that ‘Julius Caesar’ is largely based upon historical events. Whereas ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’ are almost entirely fictitious.

It is known that Shakespeare used and heavily relied upon several historical sources including Plutarch’s ‘Parallel Lives’, Appian’s ‘Roman History’, Suetonius’ ‘The Twelve Caesars’ and a number of medieval and renaissance English chronicles when writing ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’ and therefore had a great deal of historical insight into what actually happened.

The only truth in the tragedies of ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’ to their namesakes’ lives is a similarity to the names of people in ancient stories and history. By contrast to ‘Julius Caesar’, Hamlet’ is based on the legend of Amleth recorded by the medieval historian Saxo Grammaticus in the 12th century. ‘Macbeth’ is loosely based on Mac Bethad mac Findláich (King Macbeth of Scotland) who ruled in the 11th century.

On the aspects of Julius Caesar’s character Cassius sees as flaws and to what extent Caesar contributed toward his own death based upon evidence from first two acts of ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’ by William Shakespeare

From the very beginning of the play the reader is aware of the feelings of dissent toward Julius Caesar by senior officials and members of Caesar’s close circle. In Act 1, Scene 1 Flavius and Murellus discuss their anger and unease regards the general public’s ‘ingratitude’ for that which Pompey did and the power Caesar has attained and is in their view abusing. However, they do not necessarily identify specific flaws in his character.

In addition, at the beginning of Act 1, Scene 2 following the soothsayer’s warning to Caesar to ‘Beware the Ides of March’, Caesar calls the soothsayer a ‘dreamer’ and casts aside the words of warning. Here it is important to note that Roman leaders and society more widely usually gave great credence to the words and prophesise uttered by soothsayers. They were considered a very important part of Roman life and society. This makes even more pertinent the fact that the leader of Rome, a city guided by seers, should simply cast aside such a warning. I think it is evidence of a certain ignorance and naivety on Caesar’s part that he should so readily do so and reinforces aspects of his character that are portrayed as and may be seen as flaws that contributed toward his eventual downfall.

Moreover, when the extended monologue between Brutus and Cassius ensues, they (predominantly Cassius) reveal their first insights into that which they think makes Caesar a man with many flaws who is unfit to rule. Initially, Cassius tells Brutus that he does not believe Caesar is in any way superior to any other man or to either of themselves: ‘I was born free as Caesar, so were you: We both have fed as well, and we can both endure the winter’s cold as well as he’. He then narrates a story in which he and Caesar attempted a swim to a ‘yonder point’ ‘upon a raw and gusty day’; in an expedition initiated by Caesar. ‘Accoutrèd as [he] (Cassius) was’ he (Caesar) ‘plunged in’ and ‘bade him follow’. ‘But ere [they could] reach the point proposed, Caesar cried: ‘Help me Cassius or I sink!’ Cassius tells Brutus he helped ‘the tired Caesar’, who ‘Is now become a god’. Cassius proceeds to tell of ‘when he [Caesar] was in Spain, And when the fit was on him I did mark how he did shake, His coward lips did from their colour fly’ and later, ‘it doth amaze me A man of such a feeble temper should So get the start of the majestic world And bear the palm alone’.

*’pseudo-Corbulo’ bust most likely depicting Cassius, 1st century AD

From this, one is given a profound insight into what, in Cassius’ view, makes Caesar a man who is not great nor as virtuous as others believe him to be and who is not fit to rule. It is implied that Caesar’s decision to swim on such a ‘raw and gusty day’ is not one a wise and temperate man would make under normal circumstances. Rather, Cassius suggests Caesar is a man governed by impulse and poor decision making. Moreover, Cassius directly states using both his weakness in water and his illness in Spain as evidence, that Caesar is a weak man, feeble in body and soul who relies upon others for support and then scorns them, behaving ‘as a sick girl’. Cassius identifies these as faults based upon his own experiences with him and uses them as basis for the judgements he makes and relates to Brutus. He paints Caesar as weak, tempestuous, unwise and suppliant and expresses his disdain that he should have risen so high above those he (Cassius) views as his (Caesar’s) equals, he and Brutus included. Phrases such as ‘Age, thou art shamed!’ and ‘Rome, thou hast lost the breed of noble bloods’ emphasize Cassius’ disgust that society regards Caesar so highly as someone holy and fit to rule.

Later in the act, Caesar has a passage of dialogue in which he expresses to Antony his concerns about Cassius and what he thinks his intentions may be. He says, ‘I do not know the man I should avoid better than that spare Cassius’ and recognises his intelligence and powers of observation. The line ‘Such men as he be never at hearts ease Whiles they behold a greater than themselves and therefore they are very dangerous’ powerfully hits home the serious concerns Caesar was having about Cassius. Moreover, he was right not only to be so overtly suspicious but was also correct in his analysis of what drives such men as Cassius. It is nevertheless true that one may call Caesar foolish for not having acted upon these suspicions sooner, wherefore the danger would’ve been eliminated. After the event, even a fool is wise. *

*From Homer

On how Cassius manipulates Brutus in his speech in Act 1, Scene 2 (lines 140-168)

In this speech, Cassius uses several clever rhetorical devices to manipulate and persuade Brutus to join the conspiracy to kill Julius Caesar. He emphasizes his view of Caesar as a man who has elevated himself to a position to which he does not belong and has no right to inhabit. The phrase ‘Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world/ Like a mighty Colossus’ is evidence of this.

Moreover, he introduces to Brutus the question of why Caesar should be regarded as superior to ‘we petty men’ who ‘Walk under his huge legs and peep about’. He says that it is unjust and not right he should soar so high above them, retelling events to make Caesar look weak, undermining his status as a hero. He tells Brutus that they should not let their fates and that of Caesar remain in the hands of the gods, rather, they should take actions of their own because, Cassius says, ‘Men at some time are masters of their fates’.

Cassius makes sure to draw a direct contrast between Caesar and Brutus. In doing so, he appeals to one of the most prominent aspects of Brutus’ character, his ego. ‘What should be in that ‘Caesar’?/ Why should that name be sounded more than yours’ is a phrase Cassius knows will make Brutus think in terms of his own personal qualities. Cassius identifies the aspect of Brutus’ character which makes him resolute and isolated in his thinking and pounces upon it. He makes Brutus wonder whether there exists that much disparity between he and Caesar, and if not, then why should he be regarded as so much more virtuous than he.

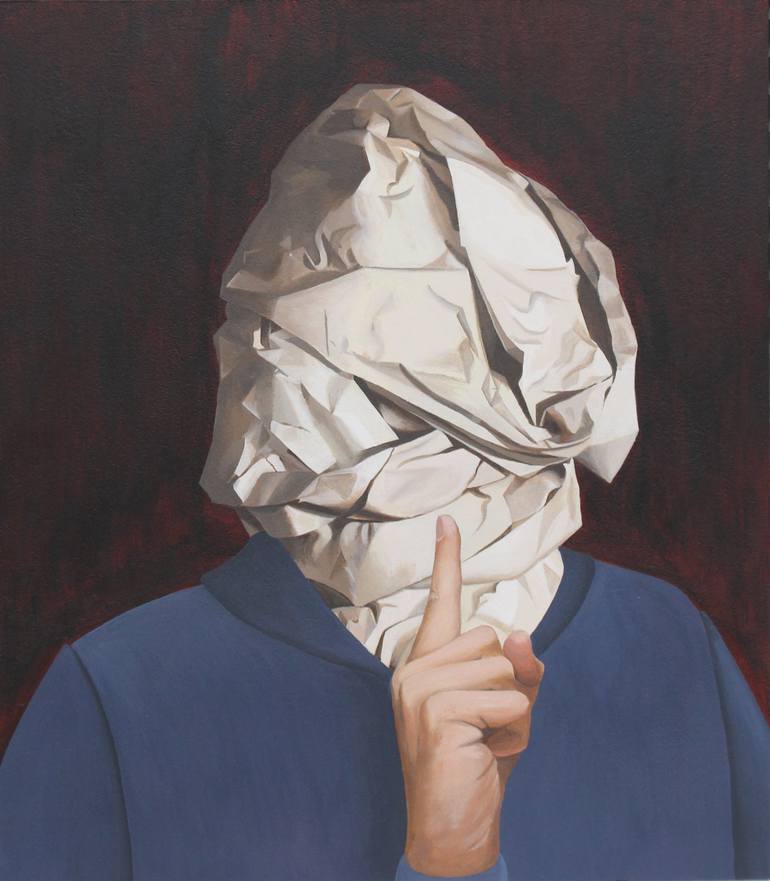

*’The Ideologist’ by Matthias Kreher, 2021 AD

Cassius seeks to appeal to Brutus’ pride for his country and asks him remember a time before Caesar; and of the role Caesar has played in Rome’s worsening condition. ‘Age, thou art shamed’ he says, ‘Rome thou hast lost the breed of noble bloods!’. Cassius makes Brutus believe he is one of Rome’s potential saviours using flattery. Rather than presenting the conspiracy as an act of murder, he frames Brutus’ joining as a noble and urgent duty he must perform for the people. He knows Brutus has a tremendous love of the state which he serves and in the final line hits home the fact that Caesar’s rise has meant a weakening of the influence of Rome’s lawmakers, of which Brutus is one; ‘When could they say, till now, that talked of Rome,/ That her wide walks encompassed but one man?’.

Cassius makes full use of his friendship with Brutus and his knowledge of his character to manipulate his thinking. He knows the things that affect Brutus the most; a sense of inferiority, a desire to be highly regarded, a love for country and an anxiety surrounding his fate. Cassius also understands that Brutus is affected more by moral pressure than by personal gain. He recognises that Brutus is acutely aware of how the Roman people view him, angling his rhetoric so that it appeals to these sensitivities. Throughout, Cassius abuses the trust and respect Brutus has for him to serve his goals.

Shakespeare presents Cassius as someone with potent powers of persuasion and very keen skills of observation. It is important to reinforce that Brutus is not a stupid character, quite the opposite. He is a man who has elevated himself to a senior position within the state and who, prior to Cassius’ trickery, displayed traits of stoicism and loyalty to certain people he held in high regard, Cassius being one of them. Cassius knows this and realises he is one of the few people Brutus will let himself be affected by. He takes advantage of this receptiveness as he does with others throughout the play, moulding their thinking as he sees fit.

How Shakespeare illustrates how persuasive speakers can influence others using the example of Murellus’ speech to the commoners in Act 1, Scene 1 (lines 35-55)

In lines 35-55 of ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’, Murellus scolds a cobbler and other tradespeople for rejoicing in Caesar’s triumph. He makes a very persuasive and forceful argument for why Caesar’s triumph is no cause for celebration. In his speech, Murellus uses several rhetorical techniques to great effect. He begins by using rhetorical questions, pronouncing: ‘Wherefore rejoice? What conquest brings he to Rome?’. In doing so, right at the outset of his speech Murellus makes his opinion of their views clear to everyone and establishes the accusatory tone the speech will take.

He asks whether there are any tributaries who think highly of Caesar now that he is stripping their powers from them, making them ‘captive’. Murellus reprimands those who think well of the situation, likening them to blocks, stones and ‘worse than senseless things’. These are very derogatory and severe words which cast a sense of impunity, seeking to make the cobbler and others who believe in Caesar feel worthless and irrational. The language Murellus uses is scornful; he makes use of sarcasm and mockery to belittle the cobbler and other workers, shaming them for their beliefs.

*’The Orator’ by Ferdinand Hodler, 1912-1913 AD

Following this, Murellus appeals to the workers’ patriotic feeling and historical memory, reminding them of their former admiration for Pompey, the man Julius Caesar has toppled: ‘Many a time and oft/ Have you climbed up to walls and battlements, / To towers and windows?’. This phrase contrasts their past loyalty to Pompey and their praise of the man who defeated him, emphasizing what he sees is their betrayal of Roman values.

Murellus uses pathos to kindle nostalgia and guilt, remembering the cheers of the public for Pompey before his fall. He stirs feelings of emotional inconsistency and shame in his crowd. As such, Murellus wraps his words in extreme hyperbole, exaggerating elements of their emotional inconsistency like their former devotion to Pompey. He weighs in heavily on this, underscoring the great extent to which their loyalties have changed. ‘Have you not made an universal shout, / That Tiber trembled underneath her banks/ To hear the replication of her sounds/ Made in her concave shores?’

Lines such as ‘Run to your houses, fall upon your knees’ are direct commands; Murellus reasserts his tribunal authority to restore discipline among the citizens. He casts their abandonment of past political imperatives as politically dangerous and tries to make them feel vehemently how severe the consequences of their fickle behaviour might be.

Comparison between Murellus’ speech to the workers and Cassius’ persuasive speech to Brutus in Act 1, Scene 2 (lines 90-131)

Like Murellus, Cassius also makes use of rhetorical questions; he tries to undermine Caesar and provoke Brutus’ emotions. In contrast to Murellus’ efforts to expose the fickleness of the workers, Cassius does not attempt to make Brutus feel guilt, he makes him think he has a duty to do something to stop Caesar’s ascent. He focuses on questioning Caesar’s legitimacy as a leader.

Pathos is as prominent an element in Cassius’ speech to Brutus as it is in Murellus’ speech to the workers. Where Murellus tries to invoke a sense of shame and make his audience feel morally uncomfortable for having abandoned their love of Pompey, Cassius makes the claim that Rome’s republican greatness is in peril and appeals to Brutus’ pride and sense of honour, particularly involving matters of the state.

Murellus’ contrasting of past and present to portray the crowd as inconsistent and disloyal to Pompey is comparable to Cassius’ contrasting of Caesar’s supposed greatness with his own personal anecdotes suggesting physical weakness such as when Caesar was unable to withstand the roaring torrent of the Tiber. Murellus shames the workers into weakening their own sense of ideological legitimacy, Cassius chastises Caesar’s abilities and strength of character to make Brutus think he is undeserving of power.

*’Demosthenes Practicing Oratory’ by Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, 1870 AD

Cassius makes use of hyperbole to enhance his speech, just as Murellus does to convey the dramatic shift in loyalty of the workers; their past cheering, he says, made ‘the Tiber tremble’. Similarly, Cassius exaggerates Caesar’s fragility and feebleness of character, describing him as trembling ‘like a sick girl’. It is important to remember that Cassius has greater leeway to exaggerate his observations of Caesar, because the person he is trying to persuade was not present during the events he claims to remember. Of course, he may be lying altogether. Murellus cannot lie nor exaggerate to the same extent simply because he is making his argument to the very people who made the sounds he speaks of.

In terms of tone, there is a clear disparity between the two speeches. Murellus’ speech is mocking, sarcastic and disciplinarian as he asserts authority and tries to make his audience feel shame. Cassius’ speech is much calmer and intimate because he is striving to flatter Brutus, using storytelling as a mode of manipulation. Phrases such as: ‘You bear too stubborn and too strange a hand/ Over your friend that loves you’ are evidence of this. There is nothing in Murellus’ speech which comes close to the softness of lines like these spoken by Cassius in his speech.

In conclusion, the two biggest differences between the two speeches are their purpose and to whom they are pronounced. Murellus rebukes the commoners to weaken public support for Caesar. Cassius seduces Brutus emotionally and intellectually in the hopes of getting him to join the conspiracy to murder Caesar. Here, a striking parallel arises. Namely, both speeches are designed to hurt Caesar in some way, whether it be emotionally or physically.

Comparison between Octavius and Marc Antony in the play

In ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’, Octavius is Caesar’s adopted heir and natural successor. He is portrayed as very diligent and controlled, one who listens carefully but speaks little. His future is Rome’s future and that is made clear, particularly toward the end of the play.

*bronze ‘Meroë Head’ or ‘Head of Augustus’, 27-25 BC

Marc Antony is shown by the events of the play to be a seasoned politician and a loyal friend to Caesar. He has clear charisma and theatricality, expressesing his love for Caesar with emotion and passion. He becomes central to the play following Caesar’s death. Antony is symbolic of the old Republic, perhaps its last great figure.

*marble bust of Marc Antony, 69-96 AD

Furthermore, when it comes to leadership, Octavius is calm and pragmatic, he shows himself to be willing to gain power by using others as part of a longer-term, thoroughly thought-out strategy. Antony often tends to be very reactive to events and driven by his loyalty to Caesar rather than a strict set of ideals. One gets the impression that his personalities’ force and vigour have precedence over a greater scheme, certainly when compared to Octavius. In this sense, Octavius leads through calculation whilst Antony does so through charisma.

Moreover, Octavius is not afraid of taking harsh actions and is not made uncomfortable by the thought of political compromise. His decision making is often ruthless, and his behaviour is that of a leader, before he even takes upon such a role. At the outset, feelings of revenge and grief drive Antony forward. He quickly accrues power through clever emotional manipulation of the public. In a sense, his volatility is what makes him so effective, even if it results in some inconsistencies. Octavius is clearly more adept and capable of adapting to a changing political landscape.

In addition to this, as an orator, Antony is highly accomplished, one might say a master. He could appeal to people on an emotional level through use of repetition and irony. And in the play, he uses these things to move a crowd to violence. Octavius is a plainer speaker, one who speaks briefly and for the most part in a way which avoids spectacle. His persuasive ability lies in the actions he takes and the alliances he forges rather than a reliance predominantly on his rhetorical ability. On a certain occasion, it may be the case that Antony’s zeal wins the crowd in the moment, however Octavian’s strategic rhetoric sets him on a better course for the future.

The bond Antony shared with Caesar was a deeply personal and affectionate one. He acts throughout his appearance in the play as Caesar’s avenger, he who will right the wrong done to Caesar the man, not necessary Caesar the symbol or ideal. That is how he sees it. Octavius is a more political choice for an heir, as opposed to an emotional one. He realizes that to cement and legitimize his authority, Caesar’s name is crucial to his efforts. His appreciation of this and the way in which legacy can impact his path forward is in many ways more solid than Antony’s notion of loyalty.

Antony is very effective at instigating chaos and accelerating the engine of civil war through his rhetoric. Octavius can manipulate chaos back to order and the situations which favour him. He is the main figure in the play who foreshadows imperial rule and his power is the ruthless, efficient kind which defines a true cold-blooded Roman leader.

It is very important to note that because ‘Julius Caesar’ is a fictional work, many of the points made above which are relevant to Shakespeare’s play may not have been so relevant historically, in the actual course of events. Shakespeare changes several events and characters somewhat for dramatic effect, so historical inconsistency is something of a inevitability. For example, Augustus was only eighteen at the time of Caesar’s death and things did not move so quickly as Shakespeare portrays. He was not a fully developed statesman and took time to gain political momentum.

On what the attributes of a ‘true Roman’ are according to characters in the play

Throughout ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’, the attributes that a ‘true Roman’ should possess are agreed upon by most characters. Moral integrity is crucial; a good reputation is earned through honour. One of the big tests of character in the play is how characters respond to death. Courage when faced with the reality of losing one’s life is something Romans held in high esteem. Stoicism, a form of self-control, the mastery of one’s emotions is another. Finally, loyalty to public duty and a willingness to place Rome above personal interest is key to being appreciated as a ‘true Roman’, one who in the eyes of the people is selfless and valiant.

Brutus views a good Roman as one who reasons and is not inflamed by personal passions or impulses. He prioritises the Republic above all else and is fiercely loyal to it, more than to any individual; he is willing to sacrifice personal bonds for the ‘common good’. This vision of Rome as a set of ideals which must be protected at all costs guides his actions throughout.

*’Capitoline Brutus’ bronze bust, late 4th-early 3rd century BC

Cassius rejects fiercely inequality and tyranny. He is absolute in his refusal to stoop to any leader, even if they are widely seen as ‘godlike’. Any sense he gets that his liberty is being infringed upon he acts decisively against. These notions of resistance and individual opposition are central to what he envisages as true Roman virtue, despite the fact that they might conflict with his envious nature.

Caesar makes very clear what his notion of a ‘true Roman’ is. Indeed, in many ways he embodies it. An unwavering, fearless and strong mindset coupled with personal superiority are attributes he holds close to his heart. He believes he is destined to rule greatly, without cowardice, equating Roman virtue to personal eminence and sheer strength of character. This is, in part, where his monarchic impulses stem from.

*’Tusculum portrait’, a Roman marble bust of Julius Caesar, 50-40 BC

Marc Antony greatly values friendship and close loyalty to one’s friends. He seems to appreciate actions more than thought and moral philosophizing. This is key to understanding why he feels revenge is an excellent way to honour the dead. One gets the impression that in the play Marc Antony has little time for moral debate and favours decisive action, even if it does not align exactly with long-term strategy.

To Octavius, a true Roman is one who can settle chaotic situations and bring about stability through the efficient and tactful use of power. He defines the ideals of what is to become a new imperial Rome in which major steps will be take away from former republican notions of what virtue truly is. Octavius is not afraid to take harsh and often very brutal steps to achieve what he views as a peaceful state under his control. And the attributes he displays during this process define the new popular method of leadership.

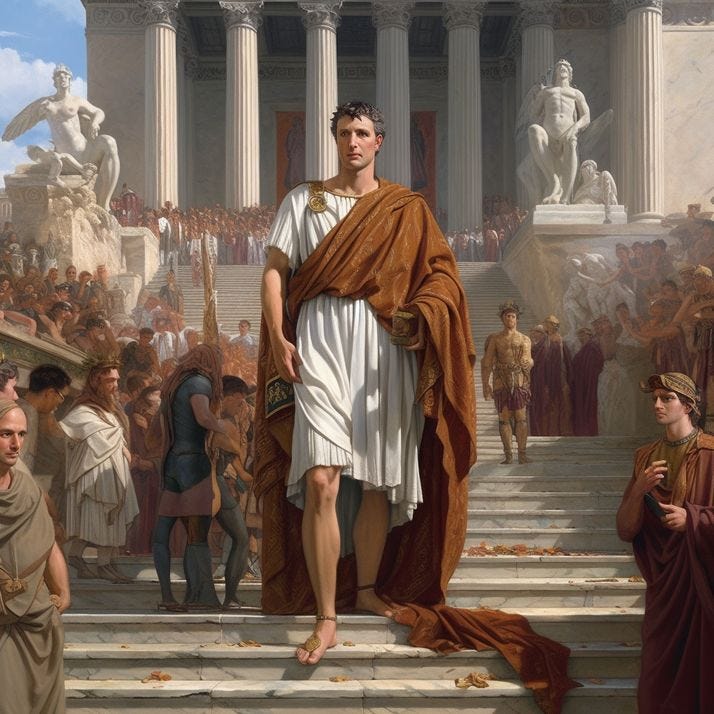

*Depiction of Augustus

All of these examples of how the play’s main characters define a ‘true Roman’ and the differences between them is evidence that Shakespeare does not specifically define a single definition absolutely. What is clear is that all of the characters listed above believe themselves to fulfil their criteria for what makes a ‘true Roman’ and that unity is altogether impossible when values conflict to the extent that theirs do. This is one of the central reasons for the fracturing of Rome’s identity during the play; the axial moral and political lines diverge too severely to allow for harmony of any kind. So whilst most characters agree on the labels, the outlines of Roman virtue, they fundamentally disagree on what those words require in practice and how these words are truly defined.

On what role the people of Rome played in its transition from a Republic to an Empire in the play

Toward its end, the Roman republic faced several large crises. Corruption, economic inequality and civil wars contributed to a feeling amongst ordinary Romans of disillusionment with the state and a greater interest in living a stable and protected life. Prominent political figures from this time such as Caesar, Octavian and Pompey gained popularity in part by presenting themselves as champions of the people. Julius Caesar was particularly successful at winning mass support through his public games, debt relief, land reforms etc. which made it much easier for him to intimidate or even bypass the Senate. His is just one example of how people allowed for extraordinary power to be accrued in the hands of individuals.

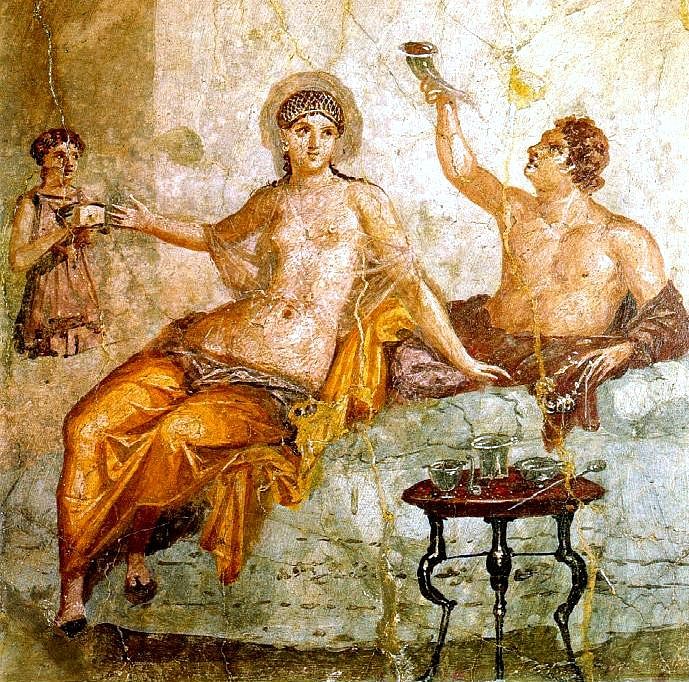

*Roman banquet fresco, mid 1st century AD

In the later days of the republic, the numbers of people living within urban spaces was very large and this population density resulted in political volatility. Political actions were often taken by crowds who wanted change, sometimes mobilized by politicians looking to pass laws, intimidate magistrates or block opponents. As a result, riots and acts of street violence were a regular occurrence, leading to the denigration of established republican procedures. It was often the case that tribunes pursuing personal gain would act ‘in the name of the people’, using this as justification for their actions. This is evidence of how destabilization of the constitutional system was accelerated by the abuse of popular politics.

*Roman fresco, a portrait of Terentius Nero and his wife, approx, 50-79 AD

Furthermore, the welfare state that had developed over time was very important to Roman people and many relied on it to live. Urban citizens were dependent on whoever controlled the supply of services such as the grain dole. Successful generals were expected to grant land to veterans who had served the state well. Public entertainment was understood to have been facilitated by benefactors rather than institutions, shifting loyalty from the Republic itself to powerful patrons.

Many Romans were in favour of peace following decades of tumultuous civil war. When Augustus claimed he was ‘restoring the Republic’ only to start an empire, the people were largely accepting of his dominance. Augustus held supreme power whilst preserving republic forms which blunted the impact of a changing state, making the transition feel gradual. As it happened, there was no significant resistance to the loss of political power, and acquiescence allowed monarchy to emerge without open revolt.

*’The Succession of the People to the Mons Sacer’, engraving by B. Barloccini, depicting the first secessio plebis, 1849 AD

As such, it is crucial to acknowledge that which the people did not do. Movements to abolish the Republic were non-existent, constitutional theory was not well understood, and manipulation of voting assemblies was easy as gatherings became largely symbolic.

It is reasonable to conclude that popular behaviour enabled a transition by elites from Rome the Republic to Rome the Empire.

On how loyalty is portrayed by characters

In ‘The Tragedy of Julius Caesar’, the greatest tension between characters that exists is that between those with loyalty to Rome as opposed to those with loyalty to individuals. To justify his actions to himself, Brutus states that killing Caesar was an act of loyalty to Rome. Cassius makes the point that freedom should never be outweighed by personal loyalty. And Antony, despite a politically dangerous situation, remains loyal to Caesar as a friend. Their examples point towards the notion that conflict erupts when there is a disparity between how characters define what loyalty is.

The idea of Rome as a great state is something Brutus is unwaveringly loyal to. The esteem in which he holds republican ideals outweighs his love of Caesar as a man. In this way, his loyalty is of a philosophical and abstract kind rather than personal. In the play, one of Brutus’ greatest errors is underestimating political reality and human emotion when making decisions. The message Shakespeare is trying to convey is that if real relationships are ignored and cast aside, loyalty to rigid ideals can become inhuman and immoral.

The nature of Cassius’ loyalty is unstable. Caesar’s power produces feelings of fear and envy within his heart however much he claims loyalty to Rome. Cassius’ loyalty to Brutus stems from his getting on board the conspiracy and giving it greater weight and legitimacy. Once Cassius realises he is defeated, he quickly gives into despair, suggesting a certain weakness of character. In essence, Cassius does not hold loyalty high as a principle, he uses it as a tool.

Personal loyalty is most transparent in Marc Antony. When he speaks at Caesar’s funeral, he is risking his life. This highlights the extent to which he is motivated by revenge and a devotion to Caesar. In the end, the speech he gives fuels civil war and national chaos. Antony’s loyalty is presented as the politically perilous yet emotionally powerful kind.

Pragmatic is perhaps the best way to describe Octavius’ loyalty. He is not as loyal to Caesar the man as he is to Caesar’s legacy. When it is useful to him, he chooses to form alliances and is not afraid to sacrifice other members of these alliances in his quest for power. It is often the case in Julius Caesar that political calculation is what loyalty to somebody, or something evolves into when the rubber hits the road. In many ways, this is a symbolic reflection of Rome’s future.

The people Caesar trusts most in the play are those who betray him. Loyalty is the smokescreen the conspirators use to justify their betrayal and Caesar’s death is evidence of how trust in politics is perilously fragile.

On the role of women in the play

The themes that dominate Julius Caesar in the main are politics, war and reputation. Roman society is presented as intensely masculine. Women are confined to the sphere of privacy, a position from which they are receptive to danger which the males often ignore. In the play, honour, rationality and stoicism are the themes men mostly associated themselves with. Women are shown to have attributes of intuition, emotion and domestic loyalty. Throughout, when men dismiss things women say as ‘feminine’, they are often disregarding the wisest voice in the room.

*statue of Vibia Sabina, Emperor Hadrian’s wife, 130-136 AD

A character like Portia, Brutus’ wife, challenges Roman gender norms. When she reasons with Brutus, she does so logically and intelligently rather than emotionally. Before Brutus even tells Portia about the conspiracy, she senses the fact that he is involved in something which troubles him greatly. To prove she can keep secrets and endure pain, she goes as far as to wound herself. Brutus believes that he can isolate his personal bonds from his political duty. He is ultimately proven to be wrong, but it is Portia who exposes this flaw in his character. One of the play’s most tragic events is her suicide. It represents the consequences of rigid political idealism and the dismissal of women who could share in civic responsibility and be effective were it not for the prejudices of a male dominated society.

*Roman marble bust of a woman, probably Otacilia Severa, 244-249 AD

The role of Calpurnia, Caesar’s wife, in the play is very different. Throughout, she expresses her emotions freely to Caesar and makes her intuitions known. The dream she has accurately foretells her husband’s death, which shows her awareness of the danger the Senate might pose. For a time, she convinces Caesar to stay at home and not go to the Senate, a remarkable feat giving his usually unwavering character. The warnings she issues are not adhered to, they are ignored, overturned by masculine pride. Caesar eventually dismisses her as he does not want to appear affected by fear, which in the end proves a major error. Whilst she is shown to have a degree of influence, she is powerless to push back against her marginalisation, and her instinctive wisdom is ultimately ignored.

*Roman marble bust depicting Livia Drusilla, wife of Emperor Augustus, 14-19 AD

In the cases of both Portia and Calpurnia, truth is spoken. However, their views are either ignored or overridden as they are excluded from the process of decision making. Their examples point toward a pattern of cases in which the collapse of Rome’s republic is tied to the systematic dismissal of domestic council and empathy.

Even though there are very few women in the play, their role is quite significant and there seems to be a suggestion on Shakespeare’s part that a society which excludes women’s voices is fragile and dangerously incomplete, one which can very easily result in tragedy.

Copyright 2025 noaxlp.co.uk