The Origin of Sacrifice

The Romans believed that before humanity came to being a great battle was fought between the Greek gods and the Titans. Many Titans were killed or sent to the underworld. Prometheus, a Titan whose name stated that he could see into the future, teamed up with his brother, Epimetheus, and decided to fight alongside him on the side of the gods. Zeus was very happy about this decision and thanked them by granting them the task of creating all living things.

Epimetheus was to share out the gifts of the gods to the beings. He gave them abilities that would allow these creatures to fly like bids, swim like fish, and to run like tigers. Prometheus began to craft and mould the first humans and their bodies, their hands, their heads. He made them in a similar fashion to the gods. Zeus however, stepped in because he did not like this idea and said that Prometheus was to make these new beings’ mortal and did not want them to be too similar to the gods. Zeus wanted humans to be vulnerable to many things and wished them to be dependable on the gods for protection and survival. Prometheus did not agree and believed that they should have a different purpose.

*’Sacrifice to the Genius Augusti’, built approx. 62 AD, at the Temple of Vespasian in Pompeii, Italy

Zeus wished to know how Prometheus would approach sacrifice with regards to humans. Prometheus believed that humans should have an advantage to begin with and be able to thrive, so he thought of a plan.

The execution of Prometheus’ plan took place at Mecone, a location where humans and gods gathered to determine the right division of sacrificial offerings. Prometheus slaughtered a bull and divided it into two halves. He would present both halves to Zeus and ask him to choose one in order to determine which one would be the gods’ rightful share in all future sacrifices. On one half he would hide the juicy flesh and meat underneath the gross and stinky stomach. On the other half he would hide the bones underneath a slab of appealing and juicy fat. When Zeus chose the second, the most appealing choice for himself, he was extremely angry at Prometheus’ tricks and deceptive craftiness. Even more so after having found out that the humans received the first and nicest meal. This choice set the precedent that, in all future sacrifices, humans would consume the best meat while offering only bones and fat to the gods.

Enraged and fuming Zeus banned fire on earth and declared it be used for no purpose, especially the cooking of meat. Prometheus did not agree with this decision, the denial of food to his creatures was something he was unwilling to tolerate. He decided that he would climb the great Mount Olympus to steal fire from the workshop of Hephaistos and Athena, then hide the flame in a hollow fennel stalk, scaling back down to deliver it to his beings. He believed that by doing this his creatures would be able to survive and prosper. They could dominate nature and its order. Not only would humans survive, but they could forge arms and wage war. Because Prometheus had provided his beings with fire civilisation progressed rapidly. Zeus, upon seeing the humans, was extremely angry and realised the consequences of Prometheus’ actions. His pride and dignity was destroyed because of Prometheus’ trickery and deception.

Therefore, in his first act of retaliation, Zeus created the woman Pandora, the first of her gender, bestowed with great beauty by the gods. She carried with her a jar containing all the evils of the world. He sent her down to earth for Prometheus to marry. Once Prometheus had married Pandora, she took the lid off the jar she carried and everything bad and evil was cast upon the humans. This divine trap wrought suffering, death and disease upon humankind. As a punishment for his defiance, Prometheus was chained to the side of Mount Olympus for eternity. Each day a vulture would come to tear out his liver, which would grow back each night again and again to be attacked again and again by the vulture. This cycle of torment was ever-present and lasted for many ages until Herakles freed Prometheus as part of his final labour. Prometheus was for so long in unbearable agony, yet he never regretted his decision to grant his beings with fire. His resilience in the face of oppression made him a beloved figure in mythology, celebrated for his spirit and personality, and for the power and progress humans received because of him. Prometheus is a symbol of our dominance over nature and our willingness and ability to utilise it.

The trick Prometheus performed at Mecone not only symbolizes the establishment of the ritual structure of sacrifices that would go onto become the cornerstone of all religious practice in the ancient Greek world but also calls attention to Prometheus as a momentous figure of defiance and prodigious intelligence.

So, the gods receive their due – bones and fat – which acknowledges their power to eat what humans cannot and also to ensure their favour. Meantime humans receive the benefit of that which they can consume -cooked meat – underpinning their dependency on the gods whilst allowing for the participation in shared ritual. This emphasizes hierarchical difference and tension between the high, mighty, divine, and immortal gods and the human beings, the mortals. The gods were given the pieces of the body that the humans could not eat (not requiring sustenance), a symbol of their divinity and status. The humans (those bound by mortality) requiring sustenance are only able to eat the edible sections, they could not eat what the gods could. However, it provided humans with the nourishment they required. Swings and roundabouts. This divide between the gods and the humans they saw as eternal and everlasting; those reigning above received offerings, whilst those below, despite benefitting from sacrifice, remain ancillary to the gods’ will.

Rome’s Water Supply System

The Romans thought that it was crucial for the well-being and safety of Rome and its people to maintain a clean and sanitary water supply system. Many societies in recent times consider freshwater a given so it is easy to assume that societies long ago did not maintain the standard of water cleanliness that numerous have today. This assumption would be a very fair one. However, their standards may not have been as bad as some may think.

The Romans were very competent and revolutionary people and excelled in creating means to make Rome and surrounding areas a better place. Their water system is just one example of their excellence in such matters. They went to great lengths to provide these services which resulted in some incredible pieces of architecture and civil engineering, an example of which is explained below.

To begin with there is the means by which the water entered Rome itself. To start with, the Romans used water that was locally sourced, from springs and wells. After this came the construction of colossal aqueducts fashioned from lead, stretching across miles of open land, following the downward gradient of the hills and mountains, utilising gravity in such a way as to keep the water flowing at a constant and steady pace. The aqueducts opened the gateway for water to come from elsewhere in Italy.

*’Aqueduct near Rome’ by Thomas Cole, 1832 AD

By the time construction was complete Rome had a plenty supply of water flowing from nine aqueducts each with their own source. The people required vast amounts of water for their various public spectacles and leisurely activities that they had become accustomed to, including the magnificent water fountains and public bathing areas. It would’ve been a humanitarian disaster if water was in short supply!

The material predominantly used in the construction of the aqueducts was lead. Lead is a substance that if consumed in high quantities can poison and cause sickness. However, the Romans ensured that the water travelling through the aqueducts whose motion never stopped, making accumulations very rare occurrences and was (with the exception of a few incidences) safe.

The Romans were in many ways a revolutionary society in the sense that they had a special aptitude for harnessing nature and using it to their advantage.

I also think it is necessary to make the point that the water in the aqueducts was not perfect. How could it be?! However, the Romans ensured that it was as clean as possible. To do this they meticulously examined the quality of the water coming into the city, tasting, smelling, and assessing to check for abnormalities.

In conclusion, Romans laid the groundwork for systems that we use today, ensuring decent and high quantities of water all year round.

2023-

How Virgil effectively makes the tale of Herakles vs Cacus one of good vs evil.

To begin, Virgil paints a despotic and vehement picture of Cacus and the cave he inhabits. Long sentences are used to convey the true extent of Cacus’ wickedness. Virgil uses Cacus’ dwelling ‘where heads of men are nailed to the doors’ as a symbol of his evil. Moving on, Virgil introduces Herakles as ‘the greatest of avengers’ having just conquered Geryon, ‘driving his great bulls along as victor’. The conflict begins when Cacus, ‘his mind mad with frenzy’, steals four of Herakles’ finest bulls, dragging them by the tail (so as to not leave forward footprints) into his cave. It is worth noting here that it is not Herakles who initiates the battle. This time he is not on a mission set for him and in the pursuit of evil. Instead, he stumbles across it, bearing the fruits of his previous labour (the cattle of Geryon). Cacus throws the first punch and disrupts Herakles’ triumphant return home.

Next, Virgil relates to us how, as Herakles was preparing to leave the spot where he was pasturing his cattle, a number of them lowered and one of the stolen heifers returned the call, ‘foiling Cacus’ hopes from her prison’. Realising he had been done an injustice, a great afront, ‘with his indignation truly blazed, with a venomous dark rage’, Herakles starts with weapons in hands, toward the source of the complaining heifer in the mountains. Here, Virgil presents a virtuous and noble Herakles having realised he has been wronged, attempting to stifle the source of the injustice. Mark that Herakles is swift to respond, he does not ponder nor procrastinate. Instead, he shows his reactionary side, a quickness to show agency. Granted, in the heat of the moment he is not portrayed as cool-as-a-cucumber, considered and deliberate. Such an approach would not bear fruit against such an unearthly creature as Cacus. Herakles realises from the outset that no approach other than unrestricted, wild and bombastic force could counter an equally wild and bombastic oppressor.

*’Landscape with Hercules and Cacus’ by Nicolas Poussin, 1656-1659 AD

Then it is descried how, when Cacus saw a vehement and highly charged Herakles hurtling towards him, he fled ‘swifter than the East Wind, heading for his cave: fear lent wings to his feet’. What Virgil implies in this sentence is that even the most hedonistic of all villains in the world has not the nerves nor guile to withstand the mere aspect of a Herakles without moderation. This is undoubtedly a heroic depiction of Herakles (the good) seeking to counter oppression from Cacus (the bad and most certainly ugly) tyrant. Whilst this is most definitely the case, Virgil also seeks to portray a Herakles showing very human emotions in his quest for vengeance, anger without moderation, resistance against maltreatment etc.

Cacus locks himself away in his cave where he secures the entrance and sees Herakles arriving ‘in a tearing passion, turning his head this way and that, scanning every approach, and gnashing his teeth’. Virgil tells us how Herakles was ‘hot with rage, three times he circled the whole Aventine Hill, three times he tried the stony doorway in vain, three times he sank down exhausted, in valley’. Here, the repetition of ‘three times’ seeks to convey the willpower and effort Herakles puts into trying to reach his enemy, the lengths of strenuous effort he is willing to go through in order to achieve his goal, driven on by a sense of injustice and a desire for revenge. This is further evidenced by the fact that after having done all this Herakles got up and tore the roof (a sharp pinnacle of flint) off of Cacus’ cave, breaking the banks of the river, thundering the heavens and revealing Cacus ‘and his vast realm’. Following this, there is a section of description where Virgil relates how Cacus’ ‘pallid realms, hated by the gods, and the vast abyss be seen from above, and the spirits tremble at the incoming light’, signifying that Cacus was no longer hidden by darkness. In this moment, all of his evils were in this moment revealed to the world by the might of Herakles’ arm and the strength of his willpower.

Despite the fact that Cacus’ vile existence has been revealed to all, Herakles’ task is not complete. He must defeat Cacus once and for all. So, Herakles goes about unleashing his complete arsenal and raining it all down upon Cacus ‘penned in the hollow rock’. Virgil says that at this stage, ‘since there was no escape now’ Cacus began belching ‘thick smoke from his throat’ whereupon ‘darkness mixed with fire’. Effective and exciting description such as this captures a reader’s strong sense of imagination. From here, we are told that ‘Herakles, in his pride could not endure it’, indicating that he lamented Cacus exercising what power he still possessed, and that he could not withstand the sight of him any longer. So, leaping into the belly of the flames Herakles choked Cacus until his ‘throat drained of blood’. Following this, Herakles ripped the doors off the cave, further exposing Cacus’ sins. He then proceeds to drag his victim out ‘by the feet’ where in the light people gazed upon his ‘hideous eyes’ and his ‘shaggy bristling chest’.

In conclusion, Virgil’s use of extremely potent and prominent description and narration makes this a highly effective tale of good vs evil where morality and its power are on full display. It is very successful in achieving its goal of increasing Herakles’ status as a symbol of high and right mindedness in a world of corruption and depravity. 07/2025

On the effect the story of ‘Herakles vs Cacus’ would’ve had on a Roman audience

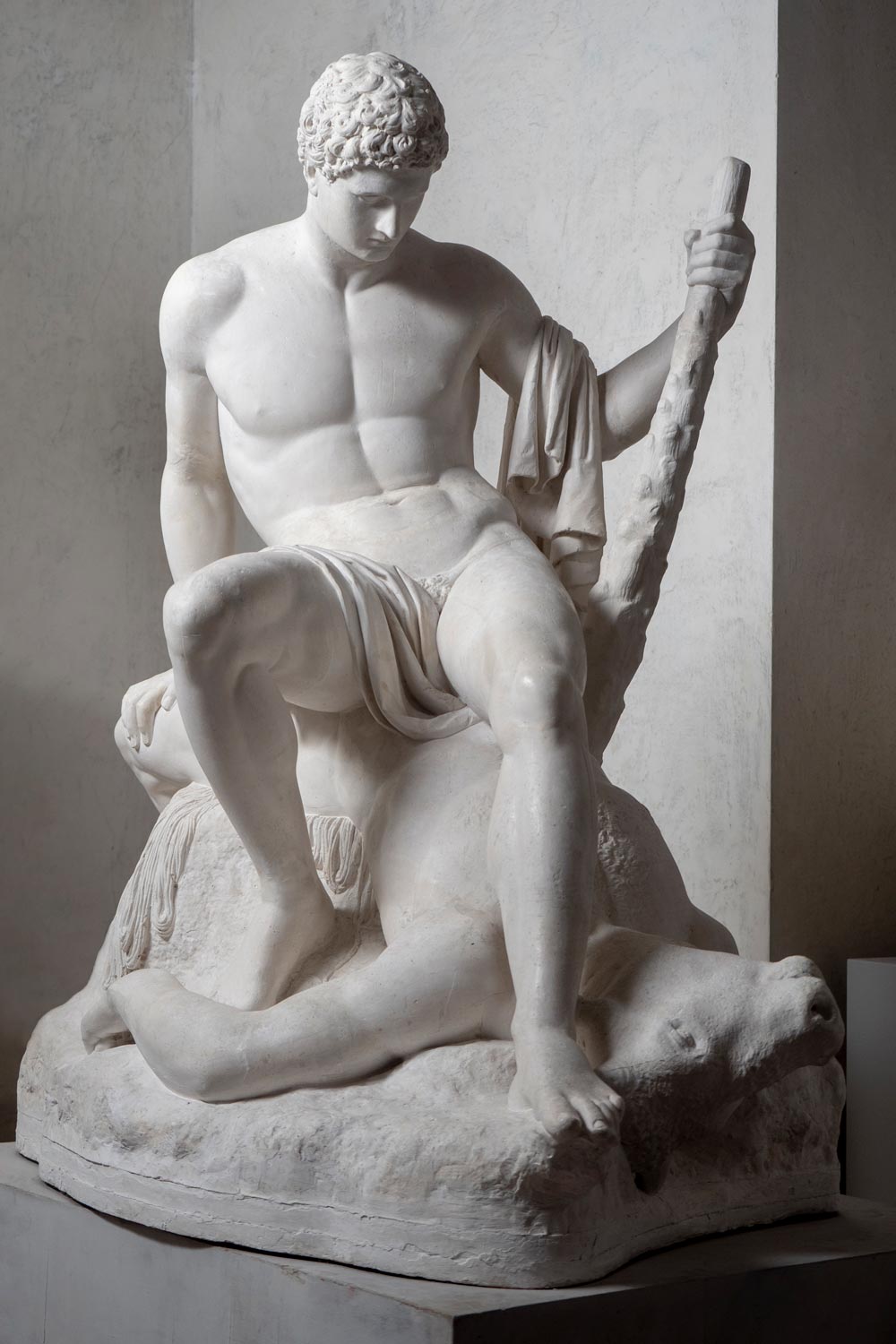

The story of Hercules and Cacus would’ve enthralled a Roman audience. The tale is a perfect representation of the notion of good vs evil, right vs wrong, virtuous vs deplorable that is found throughout ancient literature. Hercules was famed as a Roman hero in the purest sense; one who, against the odds and despite unrelenting oppression, overcame that which sought to destroy him. Cacus symbolizes the momentous nature of the tyranny Hercules frequently encountered; another obstacle to face and overcome. Moreover, the story emphasizes Hercules’ bravery and tremendous strength, idealizing him as someone capable of unparalleled physical feats. This theme of masculine strength was one that greatly appealed to the Romans, a society who revelled in practices which showcased awesome physical exploits. As such, the Romans loved action and destruction, power and brutality, they loved nothing more than seeing their favoured side win and the complete spoliation of their opponents in the process. Hercules’ violent encounter with Cacus evokes these sensibilities in a really visceral way. The qualities Hercules exhibits in the story are those the Romans admired and celebrated above all others; mixed with a great sense of pride for the founders of their society. Cacus on the other hand represents everything they saw themselves as fighting against. Stories of heroism such as this fuelled the fire of the Roman people’s hearts to keep fighting, just like Hercules.

*‘Hercules and Cacus‘ by Baccio Bandinelli, 1530-1534 AD

The Story of Romulus and Remus

Romulus and Remus are known throughout Roman mythology as the famed founders of Rome. This is an account of their miraculous endeavours.

Romulus and Remus were born in Alba Longa. They were born of Rhea Silver, daughter of Numitor, the King of Alba Longa and the revered god of war, Mars*. Prior to Romulus and Remus’ birth, Amulius had usurped the throne from his older brother, Numitor. Upon gaining power, Amulius forced Rhea to become a Vestal Virgin, a role that demands a vow of chastity. This was a move that ensured she would not give birth to potential pretenders to the throne of Alba Longa.

There are many contradictory myths regarding who the pater of Romulus and Remus was. Nevertheless, some claim that Rhea attributed her pregnancy to the miraculous influence of divine conception. During this time, it was common for the children of any Vestal Virgin who broke the vow of celibacy to be punished for their mother’s sins; so Amulius commanded that the twins be drowned in the River Tiber. However, the Servant who was sent to carry out the execution took pity on them and chose to abandon the brothers in a basket beside the River Tiber. There they remained until River god Tiberius made it so that their basket drifted down stream until it was caught by the branches of a fig tree at the base of Palatine Hill.

From there Romulus and Remus were discovered by she wolf Lupa and a woodpecker (both animals sacred to Mars) who nursed, suckled and fed them until they were found by the shepherd Faustalus and his wife, Acca Larentia. The couple took Romulus and Remus in, raising them in the way of the shepherd. One day whilst Romulus and Remus were out in the fields, they were crossed by two of King Amulius’ shepherds whom they fought which ended in Remus’ capture and detainment in Alba Longa. Amulius however, thought that Romulus and Remus were dead and did not recognise them as the subjects of the prophecy who would instigate his demise. Romulus left the wild to free Remus during which he killed Amulius and reinstated the previous King, Numitor, fulfilling the prophecy.

*’Romulus and Remus‘ by Peter Paul Rubens, 1615-1616 AD

By this time, Romulus and Remus had decided that they would build and found their own city, an act which would establish them as regional powerhouses thanks to their heroic deeds. Yet the brothers were unable to agree upon a location for their city. Romulus wanted to use Palatine Hill and Remus wanted to use Aventine Hill. To decide, they chose to utilise augury (the process by which one interprets omens) and let the gods determine the outcome. The signs came in the form of vultures; Romulus claimed he had seen 12 birds, Remus claimed he had seen 6 before Romulus had seen the same number. Once more, the twins clashed on how these omens should be interpreted and who the gods truly favoured; whether the preferences of the gods were indicated by Remus seeing 6 vultures before Romulus did, or by Romulus seeing 12 vultures while Remus saw 6.

Despite their differing ideologies and clash of opinions, Romulus began digging the foundations of a city on Palatine Hill and built a small wall to mark their physical and mental division. Remus found all of these preparations and antics truly hilarious and mocked Romulus by jumping back and forth over his wall in a humorous display. So angered was Romulus by Remus’ ridicule, he jumped back over the wall and killed Remus.in a fit of anger, thus consolidating his power. Soon after the city was named for him.

This concludes the enthralling adventures of Romulus and Remus

*The legendary myth of Romulus and Remus contains a mixture of both Greek and Roman elements and influence; by including Mars in the legend, the Romans sought to connect and associate their origins with such an important figure.

Sources: World History Encyclopaedia, Brittanica

‘Theseus vs Romulus’

The main misfortunes of the two men

It is most definitely the case that Romulus’ misfortunes began before he was born, whereupon his mother birthed two children as an enforced Vestal Virgin. A tyrannical and maniacal Amulius condemned the two babes to be persecuted for fear that a dreaded prophecy be fulfilled, so sent Romulus and his brother, Remus to die by drowning. However, by a mixture of chance and divine intervention it was fate that Romulus and Remus be saved by Lupa and raised by Faustalus. Here, it is important to note that whilst the events that led up to the brothers’ discovery were assuredly unfortunate, they experienced a great deal of fortune and favour from a number of different forces, by modes of natural and unnatural intervention. In this sense, Romulus faced a tumultuous early life, albeit one that lay the path for greatness, that fuelled many of the acts he would go onto perform. It is also worth considering that Romulus was not entirely at fault for the death of Remus. Moreover, the events that preceded the killing such as the failed augury were lamentably sequenced. However, Romulus cannot be excused for the murder of his own brother, who he had fought through so much opposition with. This is very similar to the argument that Plutarch makes regarding Romulus’ part in Remus’ death, saying ‘we more easily excuse anger provoked by a stronger cause, in the same way as being struck by a more savage blow’. However, Plutarch goes onto state that Romulus had ‘no good reason’ nor justification for ‘flying into such a passion’ due to a ‘proposal considering the common good’.

Concerning Theseus, I do not believe that many of the adventures he embarked on should be seen as misfortunes, simply because he chose to take ship of his own free will, without force from adversaries who sought his destruction. Despite this, it could be argued that whilst the pious final decision Theseus took as to his son was not a good nor well-reasoned one, the antecedent circumstances were turbulent, wreaking havoc upon his soul, the place from which all decisions are made and a situation that no demi-god of Theseus’ stature wishes to find themselves in. Considering all of this, Plutarch states that he believed Theseus wronged to a greater extent and goes onto describe Romulus’ virtue for having risen to greatness from such lowly beginnings. Furthermore, Plutarch strongly motions to scald Theseus for his forgetfulness and negligence apropos the instructions he was given in relation to change the sail which signalled he was alive and well that brought about King Aegeus’ suicide. I believe that this may be the single most tragic and unfortunate event that occurred during Theseus’ life that warrants the most heartfelt sympathy for Theseus. I do not believe that Theseus deserves a reprimand as severe as the one Plutarch delivers on this occasion. The reason being that the events in question were not entirely his fault. I think it is reasonable to say that it was King Aegeus’ haste and negligence that contributed and served as the catalyst for his own death, more so than Theseus.

*’The Tragedy‘ by Pablo Picasso, 1903 AD

Was it really not possible for King Aegeus to stop and consider the many differing circumstances and variables which meant that Theseus was not able or simply forgot to complete the task that was asked of him? Had Theseus not just performed deeds and exertions of a momentous and awe-inspiringly virtuous kind? Is it not obvious that after having done such things, he would suffer from fatigue? Plutarch does not think so stating that: ‘even with a lengthy defence and lenient judges [Theseus would] not escape the crime of parricide. I find this to be an exceedingly harsh and unfair assessment of the situation as I understand it. Plutarch moves onto reject some people’s claims that Aegeus ‘ran up to the Acropolis in his eagerness to see, tripped and fell’. This is an outcome that may be considered equally as unfortunate, but not for the same reasons. This is a version that does not attempt to cauterize Theseus to the same degree that other versions do, lowering the temperature of animosity and blame that Theseus shoulders.

In addition to this, in his assessment of Theseus’ ‘rape of women’. Plutarch makes clear that he believes the majority of these acts were done out of ‘lust and hedonism’, contrasting this with what he believes was Romulus’ relatively good treatment of the women he was associated with, making clear that Romulus’ marriage inspired enterprise and happiness. Theseus relationships? Not so much.

What causes their miseries

Either their own or others morally dubious activities and decisions. Also oversight, stupidity and poor decision making.

The reasons Plutarch gives for their misfortunes in his writings

Their characters, personality traits and the motives of their inner beings. All of these things dictate their actions and decisions, which, moreover, determine their fates as men. Plutarch toys with the notion that despite their demi-god(ly) status, they suffer from the same flaws that mere mortal men do. And it is clear that whilst Plutarch does not directly state this, he motions very strongly towards these ideas, saying: ‘It is necessary to point out that bad luck does not come entirely from divine fate, but instead to refer to the ethics and morals that exist in people’. Here, Plutarch energetically pillories Theseus and Romulus for the wrongs they have done to people in their quests for greatness, success and renown.

Does Plutarch think either of the men are not entirely responsible for their actions? If so, why?

Plutarch argues that ‘we [as a people] more easily excuse anger provoked by a stronger cause’. In this mode, Plutarch thinks that any actions taken, despite their level of morality, can be considered virtuous if they were taken in order to contribute positively toward a great and virtuous cause. Meaning that the rectitude of a particular object overweighs any potentially demeritorious actions taken in the pursuit. This conviction can be heard felt within all of Plutarch’s evaluations of the moral and ethical acceptability and amplitude in many of Romulus and Remus’ decisions and final judgements. Early 2025

Theseus and the Minotaur

Theseus and the Minotaur is a myth that is commonly regarded as one of the most poignant and awe inspiring in all of Greek mythology.

The story of the Minotaur begins with the creation of the white bull. In an attempt to impress his family, King Minos requested that Poseidon produce a gleaming white bull, which he agreed to sacrifice later on. Poseidon did so, but Minos did not honour their agreement, sacrificing a different bull. When Poseidon noticed King Minos’ treachery, he arranged for Queen Pasiphae, Minos’ wife to fall in love with the bull and to conceive a child with it.

The minotaur was the hideous, mutant child of Queen Pasiphae, wife of King Minos, who, upon falling in love with a snow-white bull, bore a child with him. This dangerous beast, the Minotaur, whose physiognomy was the head of a bull and the body of a man, was hidden away by King Minos in a complex labyrinth designed by Daedalus and his son, Icarus. King Minos and the Minotaur have a close association; the beast’s name in part is derived from Minos and the word ‘taur’ which means ‘bull’. However, Minotaur was not the name originally given to it by its mother. Queen Pasiphae named it Asterion, meaning ‘starry one’, a reference to Taurus, the ancient Greeks’ bull constellation.

The Minotaur as it grew up was forced to be enclosed within the labyrinth because he became increasingly violent and uncontrollable and could only be sated by human flesh, particularly young children. Theseus was the son of King Aegeus and had made it his life’s mission to kill the minotaur because of the horror surrounding its incarceration. In doing so, Theseus sought to put an end to the arrangement that had been made between King Aegeus of Athens and King Minos of Crete following the death of Minos’ son and other calamities. This arrangement was that Athens would send 7 young men and 7 young maidens to Crete every 9 years. These youths were intended for the Minotaur’s consumption.

Ariadne and Phaedra, the daughters of King Minos encountered Theseus on his journey to Crete and at once fell in love with him. Such was Ariadne’s love for Theseus, she implored Daedalus to help Theseus in his efforts and ensure he was not killed. Theseus took Daedalus’ advice and carried a ball of string with him through the maze so that he would be able to find his way out after having slain the Minotaur. This he did, fulfilling his quest to end the Minotaur’s reign of terror!

*’Theseus and the Minotaur‘ by Antonio Canova, 1781-1782 AD

Today, people around the world remained fascinated by the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur and its rich symbolism and imagery. Knossos Palace, located in Crete and built around 1700BC was believed to be home to King Minos and the Minotaur. The myth and interpretations of it in art can be found throughout the modern cultural landscape. Famously, Picasso was fascinated by the myth and expressed his fascination in many drawings and paintings throughout his life. One of the most famous being ‘Guernica’ (see below). More recently, the Minotaur and references to it have been featured in a number of popular films and TV shows from ‘Minotaur’ to ‘Jason and the Argonauts’. In conclusion, the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur is an ancient tale of heroism and love whose significance and impact is still felt to this day.

Eulogy for Theseus (fictional work)

‘Dear all in attendance, we are gathered here today to commend and pay homage to the great and valiant life of Theseus, son of King Aegeus of Athens, noble Aethra and divine descendant of the virtuous Poseidon. To begin, I wish to make known the fact that it would be altogether foolish and impetuous for any man to attempt a complete narration of the many reputable deeds performed by a demi-god such as Theseus within the strict confines of time. Any effort to do so would require compression, and, therefore, imprudent disregard for the task therein. With this in mind, I swear I shall truncate nothing that could serve as detriment to Theseus’ commemoration. Instead, I will relate to you my selection of a small number of his innumerable endeavours that forever changed histories’ course for the benefit of all Greeks.

It all began when King Aegeus of Athens wished to bear a child of his own. For this, he went to the Oracle of Delphi to seek advice. King Aegeus did not comprehend the prophecy he was read so he went to Pittheus of Troezen and related to him what he had been told. Pittheus understood, whereupon he presented Aegeus with his daughter, Aethra. Leaving Aegeus, Aethra journeyed to Sphairia where she was possessed and enchanted by Poseidon. From this divine mixture, Theseus was born, a wondrous and happy event.

Theseus, seraphic and empyrean of blood, destined for glory and greatness, the finest of all born on that day!

*statue of Theseus located in Thissio, Athens, Greece, 1868 AD

Before returning home to Athens, King Aegeus buried his sandals and sword under a very substantial rock, in the hope that when Theseus grew up, if he was blessed with enough might, he would lift the rock and retrieve the items beneath as a holy symbol of his deific lineage. Therefore, Theseus was raised by his mother in Troezen, and, when the time came, by the powerfulness of his might and will, he found and claimed the items.

After having done this, Theseus was told by Aethra the truth about his ancestry and that he must return the objects to his father in order to claim his birthright. So, the brave and noble Theseus had two options. He could either choose to venture by sea, the comparatively safer route, which was destined to yield few adventures. Or he could choose to travel by land and follow a perilous route, where he would encounter six entrances to the Underworld, each guarded by a chthonic enemy.

It is at this juncture that one may begin to comprehend the degree of bravery and intrepidity which shrouds all of Theseus’ miraculous deeds and exploits, for he chose to journey by land, defeating all villains that attempted to stifle his efforts. First there was Periphetes, the maniacal Club Bearer. Then Sinis, the Pine Manipulator. Next, he encountered and defeated the colossal Crommyonian Sow. Followed by Sciron, who lured his victims by asking them to wash his feet and then pushed them off a cliff to be eaten by a giant turtle. Then came Cercyon, King of Eleusis and wrestler. Finally, after having defeated these malevolent murderers for the benefit of all travellers, Theseus overcame Procrustes, the Stretcher. With the completion of these exigent exploits Theseus proved that he was strong and unassailable both in body and spirit and that he was capable of defeating and outsmarting some of the fiercest adversaries in all of Greece.

This is further evidenced by the events that followed which I will not expand upon or relate at length. All I shall say is that these events typify the greatness of the man just one of whose exploits I a moment a go narrated. You may be wondering why, out of all Theseus’ adventures, I chose to delineate this one in particular? I would answer that it is because I was present at his departure from Troezen and remember the circumstances under which he left with great fondness.

Finally, a word on Theseus’ lamentable death. He died a man having accomplished feats never before seen or heard of. He was a monumental leader and figure who brought about Greece’s societal cohesion. It is sadly true that his demise was as a result of an ignorant and unintelligent mass who failed to acknowledge the effects of decline and misattributed the blame; exiled, persecuted and ultimately killed my friend and brother Theseus. It is one of many gruesome examples of one who once did great things, beat to a pulp by those he had served and cared for so long. And all of this at a time when he was in deep mourning for his beloved son, Hippolytus.

I would like to finish this eulogy by saying that my life was made the richer for having met and spent time with Theseus and believe that the same is true for everybody else in this room. Although he searched long and hard, ultimately Theseus sadly never met his life partner and settled down. He is survived by three sons, Acamas, Demophon, and Melanippus.

May his legacy endure’.

Biographies of Ixion, Meleager, Busiris, Antaeus and Philoctetes

Ixion

Ixion’s parentage is unclear. However, he believed to have been the son of either Ares, Leonteus, Antion or Phlegyas and Perimele. He is either the father or stepfather of Pirithous; this depends upon whether Zeus was his father or not as he claims to be to Hera in Iliad. Ixion wanted to marry Dia, one of the daughters of the noble Deioneus and to secure the marriage promised treasures to his would-be father-in-law. Despite this, Ixion did not pay up for Deioneus’ daughter. Therefore, in a retaliatory effort, Deioneus stole a number of Ixion’s horses. Naturally, Ixion was furious but managed to conceal this fury and invited his father-in-law to Larissa, where a great feast was taking place. Upon Deioneus’ arrival, he was pushed by Ixion onto a bed made of burning coals and wood. As a result of this act and all of the scorning that followed, Ixion went mad. A large number of local princes were disgusted by this treacherous act which prompted them to refuse to perform rituals which would have cleansed Ixion of all the guilt bestowed upon him. From this point on Ixion lived the life of an outcast and was eschewed by everyone for his act of parricide.

*‘Ixion‘ by Jusepe de Ribera, 1876 AD

Zeus however brought Ixion to Olympus as he felt sorry for him and thought he was being treated unfairly. In spite of this great act of kindness, Ixion began to make a move on Hera, betraying and angering Zeus. In order to prove Ixion’s infidelity, Zeus made Nephele, a cloud nymph, in the form of Hera. Ixion mated with this false-Hera who bore two children. Because of Ixion’s treachery, Zeus blasted him with a thunderbolt and expelled him from Olympia forever. In addition to this, Hermes was ordered to bind Ixion to an ever-spinning fiery wheel for eternity. The only relief Ixion got from this punishment was for a brief period when Orpheus entered the Underworld playing his beautiful music.

Meleager

Meleager was the son of Althaea and either King Oeneus or Ares. This parentage made him a Calydonian prince. At his birth it was prophesized that Meleager would die when a piece of wood that was then burning had ceased to burn on the family hearth. His mother discovered this and put the fire that was burning out and then hid the hearth. His siblings were Deianeira, Clymenus, Periphas, Agelaus, Thyreus, Gorge, Eurymede and Melanippe. Meleager was married to Cleopatra. His children were Parthenopeus and Polydora. On one occasion, Meleager was sent by his father to assemble a number of Greece’s heroes in order to hunt the terrorizing Calydonian Boar. One of the many heroes he chose was the huntress Atalanta, a woman whom he loved. Having borne down upon the Boar, two centaurs attempted to rape Atalanta; therefore, Meleager killed them. Following this, Atalanta first struck the Boar, wounding it, Meleager finished it off. He allowed Atalanta the hide as she had wounded the beast first.

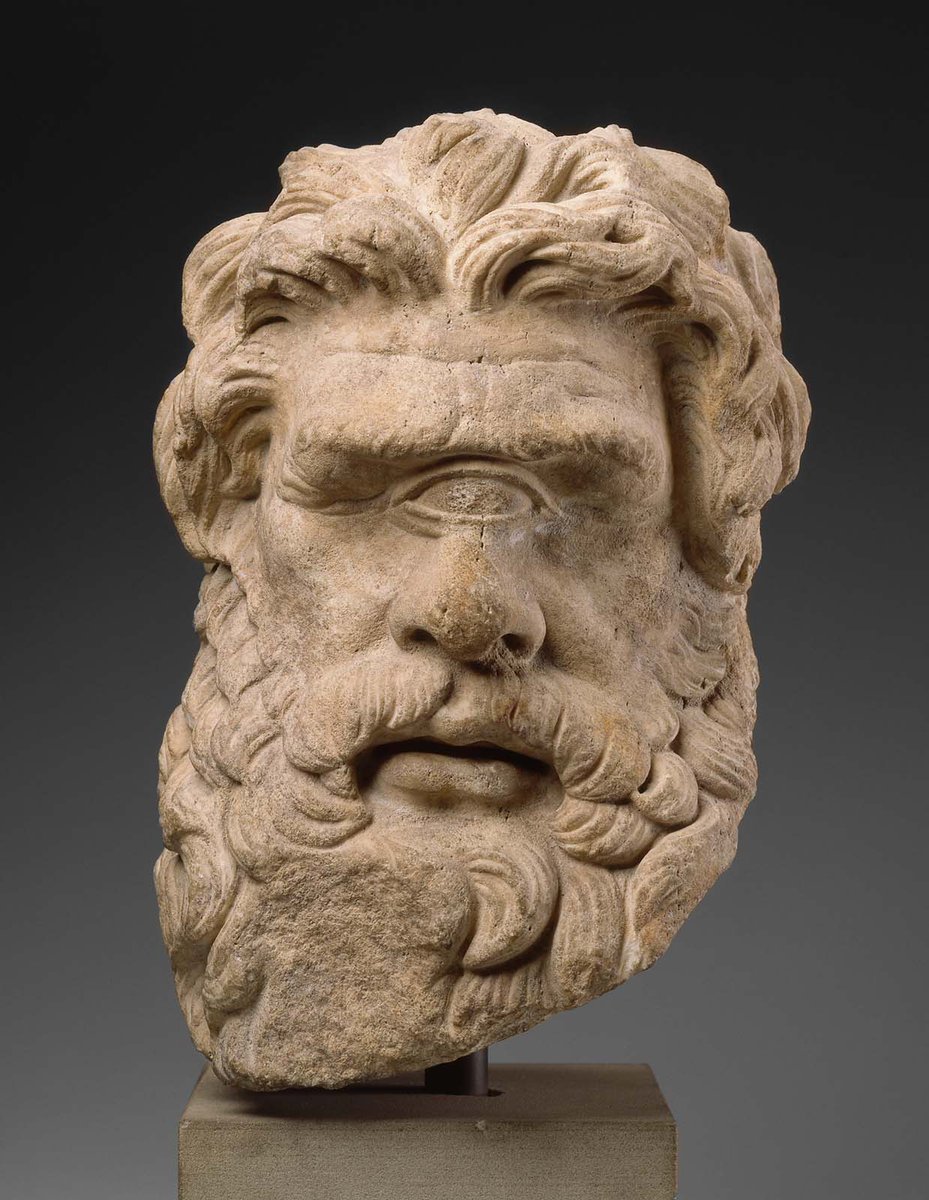

*’Meleager’, 4th century BC

Because Meleager had awarded Atalanta with the prized hide, his two Uncles Toxeus and Plexippus were furious. An argument ensued during which Meleager murdered them. This applied to all who insulted Atalanta. However, Althaea was enraged that her son had killed her brothers, so she placed the wood back onto the fire until it ceased to burn, killing Meleager and fulfilling the prophecy.

Busiris

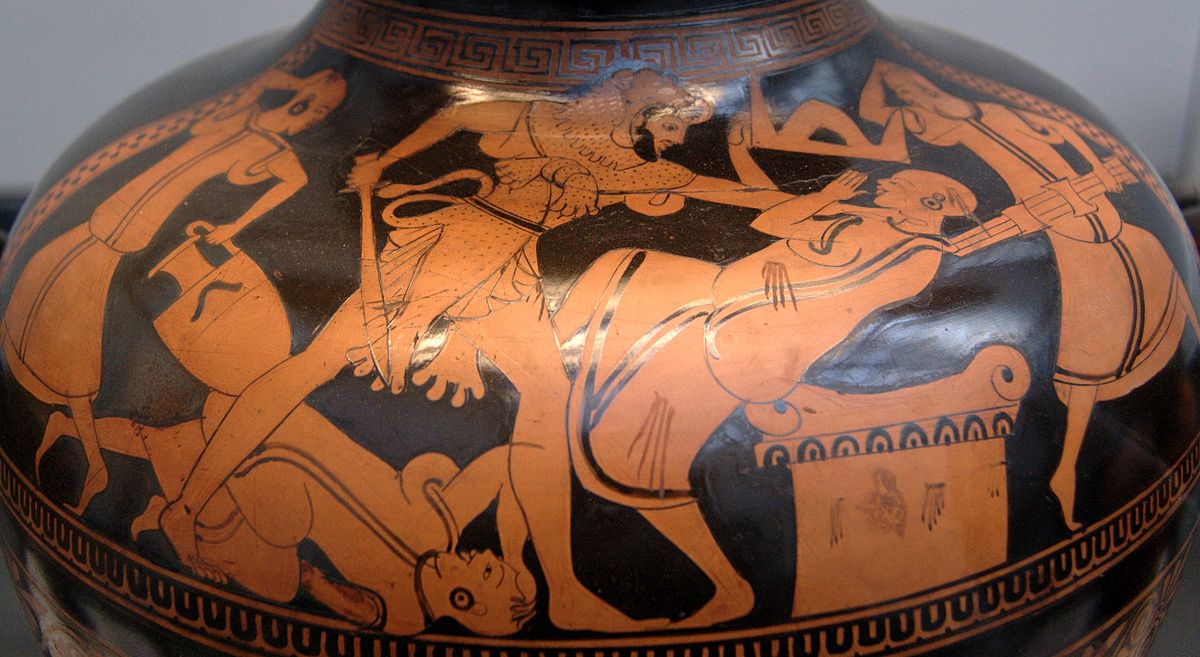

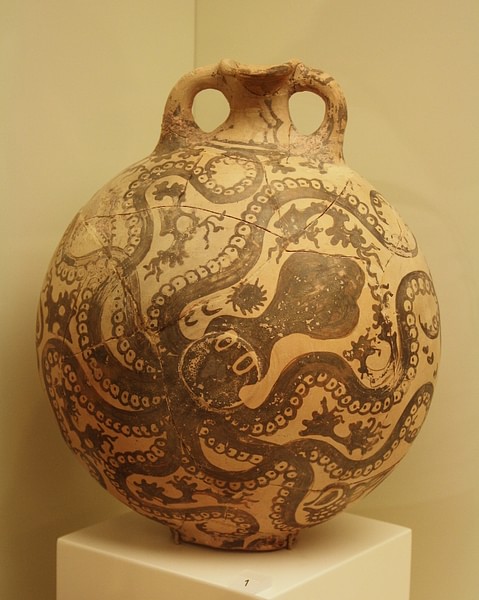

Herakles slaying King Busiris of Egypt depicted on an ancient Greek vase, 500-450 BC

Busiris was the son of Poseidon and Libya. He was the founder of Thebes’ line of Kings and Egyptian civilization’s founder. His children were Melite and Amphidamas. Busiris would sacrifice all those who visited him to the gods. On one occasion, Herakles visited him but avoided being killed, breaking out of his shackles and killing Busiris instead.

Antaeus

*’Statue of Hercules and the Centaur Nessus‘ by Giambologna, 1595-1599 AD

Antaeus was Poseidon and Gaia’s son. Antaeus lived in the interior desert of Libya. The goddess Tinge who Tangier in Morocco was named after was his wife. He had two daughters named Alceis and Iphinoe (the latter had a fling with Herakles). Antaeus had a tendency to challenge all those who passed him to a wrestling match and remained undefeated as long as he was in contact with Gaia, his mother the earth. Not only did Antaeus win against the majority of his opponents, but he also killed them (the sole exception being Herakles) using his victims’ skulls to build a temple in memory of his father. On his way to the Garden of Hesperides as part of his 11th labour Herakles encountered Antaeus and fought him. Herakles knew that he could not defeat Antaeus by throwing or pinning him to the ground. Therefore, he raised him aloft before crushing him to death in a bear hug.

Philoctetes

‘Philoctetes on Lemnos‘ by Jean-Germain Drouais, 1788 AD

Philoctetes was the child of King Poeas of Meliboea and Methone. The bow and arrows of Herakles belonged to him for a time due to the part he played in helping Herakles end the agony that the shirt of Nessus caused him. He was honoured with lighting the pyre upon which Herakles was deified indicating the high esteem in which he was held by Herakles. Philoctetes is famed as a Greek hero, having been one of the Greeks who competed for Helen’s love. Because of this he joined in the expedition to retrieve her from Menelaus which would result in the Trojan War. It was during the War that he served as an archer and killed three men. On one occasion Philoctetes was exiled by the Greeks on the island Lemnos after having been wounded by a snake sent by Hera to punish him for his helping Herakles*. The Atreidae had advised Odysseus to abandon Philoctetes; a move which made Philoctetes resent and harbour a grudge toward Odysseus. Philoctetes remained on Lemnos for a decade, during which time Medon was in control of his men. Helen, son of King Priam revealed after having been tortured that the Greeks must be in possession of Herakles’ bow and arrows in order to win the war. Therefore, Odysseus and a number of his men including Diomedes hurried to Lemnos where they were shocked to find Philoctetes alive. In a state of disbelief and astonishment, the contingent was unsure what to do. Nevertheless, Odysseus managed to take the weapons from Philoctetes using trickery, but Diomedes insisted that he would not leave without Philoctetes if they were to take the weapons. The deific Herakles told Philoctetes to leave the island and told him that he would be healed by Asclepius’ son and be honoured as a hero. Once in Troy his wounds were healed by the physician sons of Asclepius. It is in contention and is debated whether it was Philoctetes who killed Priam. Some say he succeeded in doing so after four shots hit four different parts of his adversaries’ body. Philoctetes was of the belief that they should continue in their attempt to storm the city despite initial failures. On the day of the fall of Troy, Philoctetes was one of the men who emerged from the Trojan Horse and killed many prominent Trojans. How Philoctetes died remains a mystery. Two very different versions exist: either he settled in Italy, founded cities and died of old age or he died in battle, fighting in a later war.

*There are many versions of the story in which Philoctetes was bitten by the snake, but this remains the most widely acknowledged

Early 2025

The Myth of Cassandra

Cassandra was a daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy. Hector was her older brother, famed as a hero of the Trojan War. Paris is another of her brothers. Helenus, the seer, was her fraternal twin sister. Because of her lineage, Cassandra was not only a princess but a priestess of Apollo at Troy. Cassandra foresaw that the destruction of Troy would take place and knew of the instability it would cause if Paris journeyed to Sparta and brought Helen of Troy back with him. However, Paris did so in spite of her warnings. This went onto become one of the key events that started the Trojan War.

In fact, Cassandra warned a number of different people about a number of different things in a number of different places, and none of those she advised listened to her. Her warnings and predictions were quite extraordinary and included alerting the Trojans to the Greeks inside the Trojan Horse, Odysseus’ wanderings and Clytemnestra and Aegisthus’ murder of Agamemnon and her children. She also predicted that Aeneas would survive the Trojan War and journey to Italy to found a new nation.

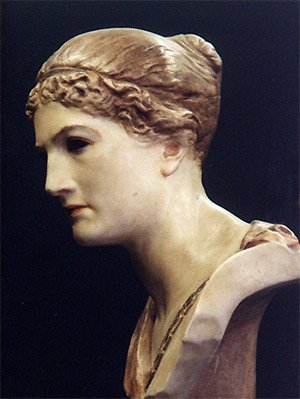

*’Cassandra‘ by Max Klinger, late 19th century

The most famous myth surrounding Cassandra involves Apollo. Apollo offered Cassandra the gift of prophecy if she would sleep with him. She agreed but after having received her gift rejected Apollo, going back on her promise. Apollo was unable to revoke a divine power, so in order to get retribution, Apollo spread the word that all of the prophecies Cassandra uttered would be false. The pain these events caused Cassandra was deep. As a result of them she was now seen as a crazy liar by both her family and the Trojan people. Her father, Priam, took the decision to lock her away in a guarded chamber where she was treated as deranged and demented. In Aeschylus’ famous work ‘Agamemnon’, Cassandra conveys her and Apollo’s relationship:

Apollo, Apollo!

God of all ways, but only Death’s to me,

Once and again, O thou, Destroyer named,

Thou hast destroyed me, thou, my love of old!

Her feelings on the matter are evident here:

I consented [marriage] to Loxias [Apollo] but broke my word. … Ever since that fault I could persuade no one of anything.

Cassandra’s efforts to warn the Trojan people about the Greek soldiers hidden within the Trojan Horse were strenuous; on one occasion as the Greeks were feasting, she attempted to make them aware of the impending danger. They however did not care to listen and began berating her. Intent on proving her point, Cassandra picked up an axe and a torch and began to charge toward the Trojan Horse in an attempt to destroy it herself. The Trojans present stopped her to the great relief of the Greek soldiers within. Othronus and Coroebus journeyed to Troy’s aid during the conflict in an effort to get Cassandra’s hand in marriage before being killed. After Troy’s fall, Cassandra went to the temple of Athena to take refuge. There she clung onto Athena’s wooden statue before being raped and abducted by Ajax the Lesser. Due to the fact that Cassandra was a ‘supplicant at the sanctuary under the protection of the goddess Athena’ Ajax’s actions were defiled and viewed as sacrilege by the gods, particularly Athena, whose temple it took place in. It was therefore natural that Ajax’s death should take place at the hands of Athena and Poseidon.

Following these events and after the fall of Troy, King Agamemnon took Cassandra in as a concubine. During the time Agamemnon was at war, his wife, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus (their servant) had an affair. It was one of these two who was later responsible for the deaths of not only Cassandra and Agamemnon but also their children, Teledamus and Pelops. Cassandra is buried in Mycenae.

A day in the life of a Flamen Martialis on duty

He awoke before sunrise and began by undergoing all of the necessary ablutions one must who is bound by sacred law. He started by bathing his hands using water supplied by a young servant boy, ritually pure because of the tenderness of his years. Following this, he began to dress into ceremonial garments laid out before him; a purple edged toga woven from the whitest of wools around his shoulders, an apex upon his head, and knot free sandals for his feet. Where his toga required fastening, wooden fasteners were fitted. He ensured that throughout the morning he would not come into contact with any impure things, ensuring his ritual purity. All of these precautions were necessary because a major public sacrifice to Mars was due to take place as a result of the Senate having declared a public holiday, so large crowds of people would soon be gathering in order to witness the ceremony.

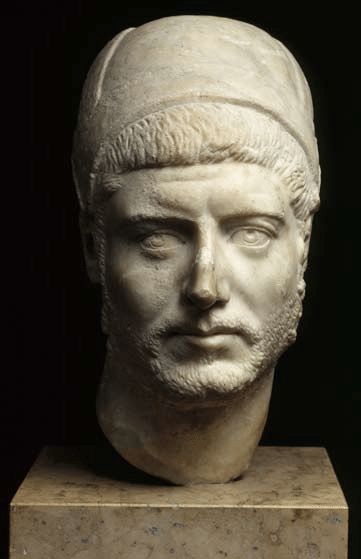

*bust of a Flamen Martialis (Priest of Mars), 3rd century AD

Leaving his home at dawn, he wandered through the Forum, engaging in respectful interactions with citizens; each person’s gaze as unique as his own, all inquiring as to a different purpose. As he walked further, he observed in the direction of the Temple of Mars, the sacrificial bull being prepared by the victimarii, an animal chosen carefully by the pontifices. He noted the bull’s perfect majesty, its sinuous form emphasized by its decoration, gold leaf and ribbons. Now at the ceremonial site, he fixed his gaze upon a nearby augur examining a flock of birds, raising his lituus to the sky and proclaiming that the auspices are favourable.

Ascending the temple’s steps, a tibicen played with a soft tone to his right, drowning out the sound of both the boisterous crowd and any potential noises the bull might make in anguish. The crowd had amassed; generals, senators and soldiers could be seen amongst them as he raised his limbs skyward and began his vehement invocation. Following this, at the altar he began to sprinkle mola salsa upon the bull’s head and the surrounding altar. Then, onto the bull’s back was poured a libation of wine and, as the animal began to nod, the victimarius stepped forward, bashing its head with a hammer before cutting its throat with a glittering bronze blade. A bronze bowl was filled with blood from the bull’s neck as the haruspex appeared, and was handed a board of warm and sultry entrails, the liver and other organs. He examined them carefully with unwavering focus and intent before he soberly proclaimed: ‘All signs are well’. The slaughter had gone smoothly, both the bull’s actions and its insides were shown to be pure and worthy of the ceremony’s proceeding.

Next, the sacred portions were burned on the altar and the smoke rose upward toward the gods. The edible meat was taken away to be shared out in a sacred feast amongst the worthy attendees. A meaty aroma began to swell. The sacrifice was complete.

The street filled with the sound of music as entertainment began in surrounding areas. Before his duty was done and he could retreat to within the temple, he recited the ceremonies’ closing prayers. His voice rang out to be received by those in the crowd with bright eyes. Afternoon had come and all had nearly reached an end. All that remained for him was to perform a number of private rites and to take account of the day’s events in the priestly annals.

As the day grew old, he enjoyed a solemn dinner with his peers before performing his final purification rituals and uttering an almost inaudible prayer to the gods to whom his day and his entire being was, and forever would be, dedicated.

Greek festivals: The Great Panathenaia and the City Dionysia

The Great Panathenaia was a festival held every four years from 566BC as a celebration of the goddess Athena’s birthday, the divine protector and patron of Athens. Every year an annual (lesser) Panathenaia was held which was much less elaborate and on a smaller scale than the ‘Great’ Panathenaia held every four years. Nevertheless, the festival was comprised of a number of religious rituals, athletic contests, musical competitions and civic celebration. The Great Panathenaia was celebrated in Hekatombion, the first month in the Athenian calendar and had a duration of up to 8 days.

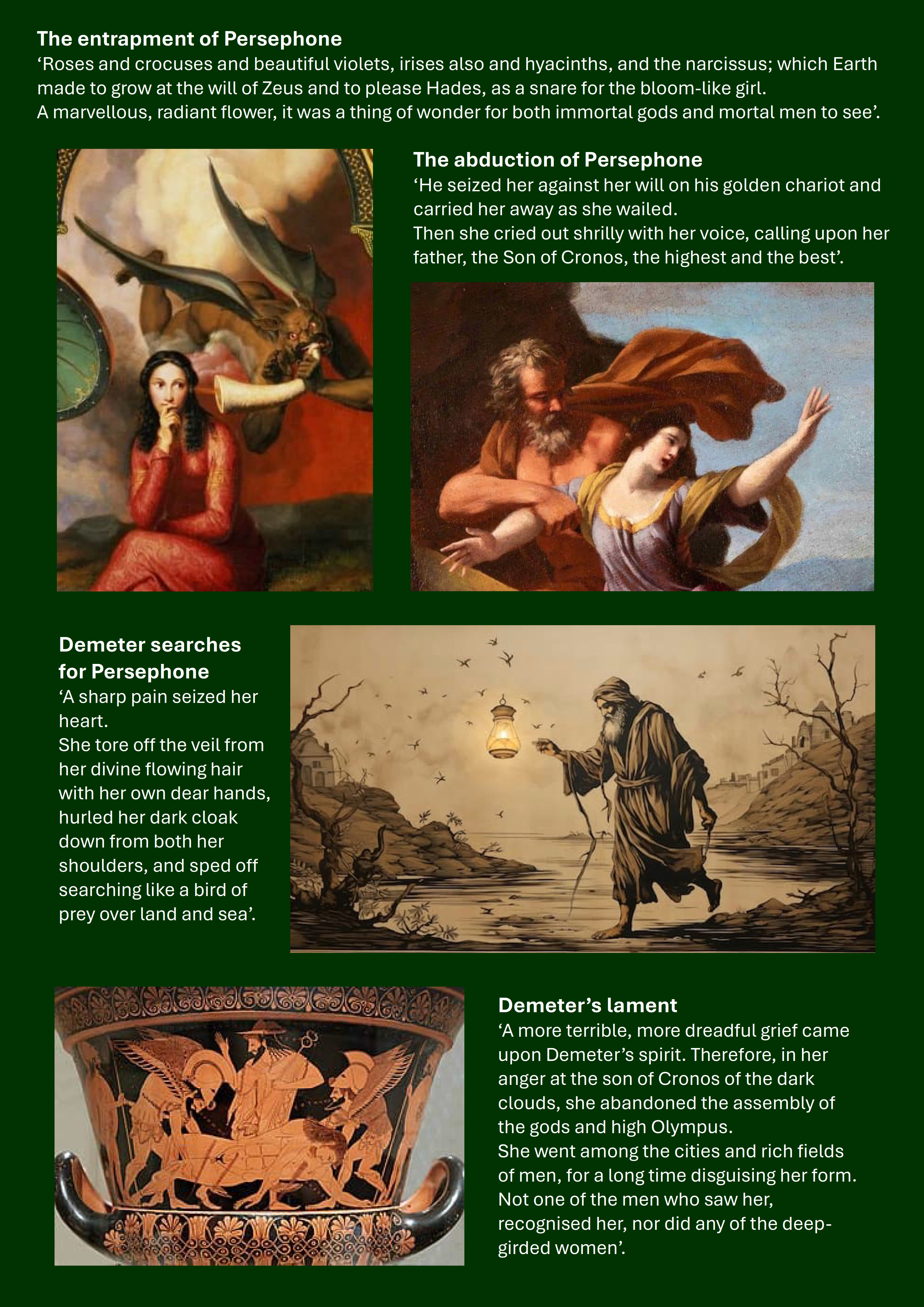

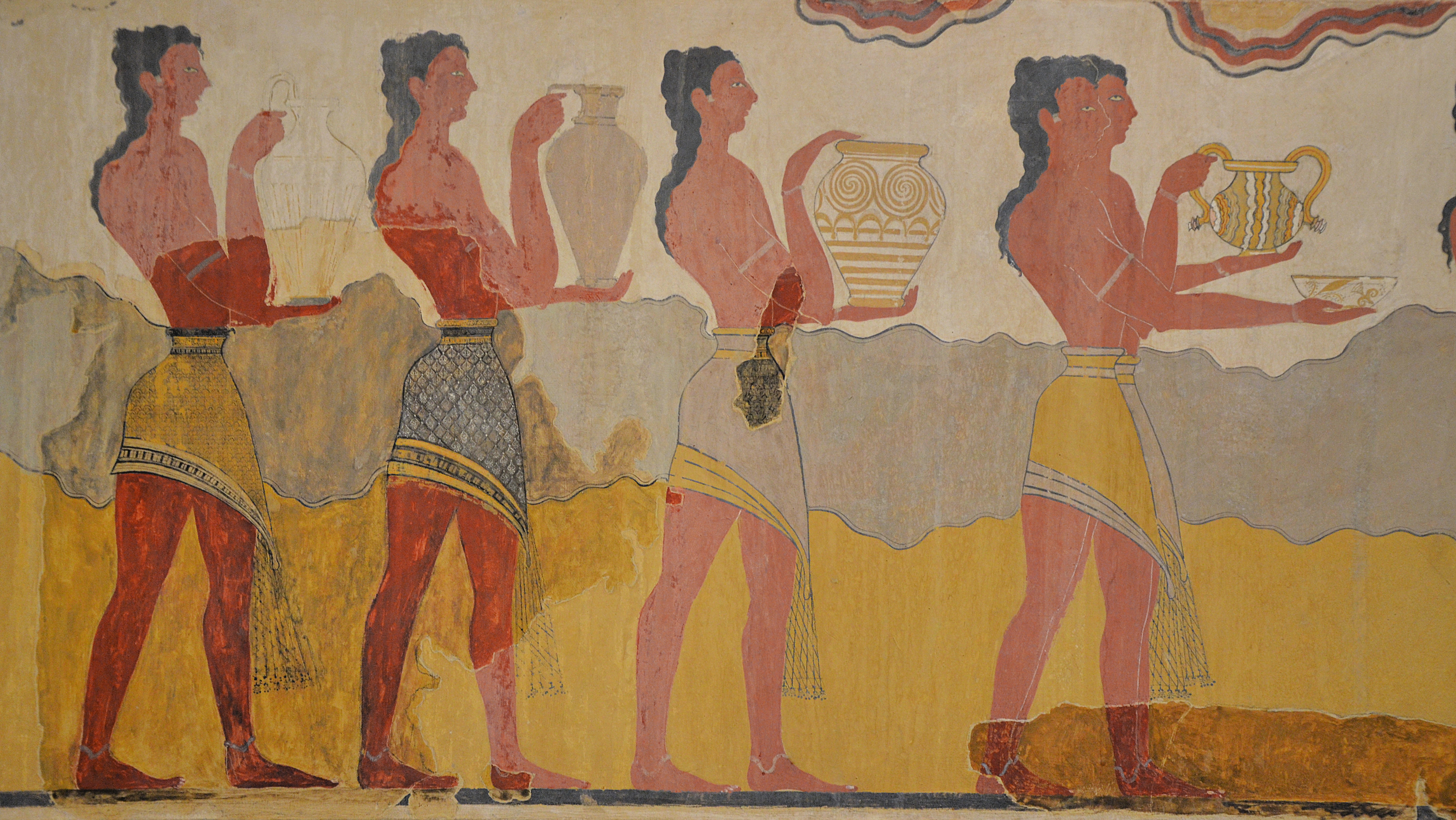

*a section of the Parthenon frieze, part of the Elgin Marbles, 5th century BC

On the first day, musical and rhapsodic contests were held. This included kithara playing accompanied by singing, aulos playing, rhapsodic recitations and competitive performances of Homeric poetry taken primarily from his great works ‘The Iliad’ and ‘The Odyssey’. These artistic events celebrated and recognized Athens’ cultural renown.

On day two, athletic contests for boys and youths took place. Such contests included wrestling, boxing, pankration, running races and pentathlon which promoted young physical brilliance and a preparedness for conflict.

On the third day, contests which took place on day two amongst youths were performed by fully grown males. These physical competitions were extremely intensive and dangerous, true displays of Roman male might and primal power. One of the prizes awarded to individuals who won these contests included a Panathenaic amphorae filled with sacred olive oil from Athena’s groves.

On day four, equestrian contests occurred, usually at the Hippodrome or other spacious, open areas around the city. Events included chariot races (between 2 and 4 horse teams), individual mounted races and apobates races, which involved a rider jumping off his horse and running beside the moving chariot before jumping back on, a remarkable feat of endurance. Those who participated in such contests were wealthy Athenians rich enough to afford horses and teams. All prizes given in these events were awarded to the owner of the horse which won, not the rider. Equestrian events were used by elites as a way of exhibiting wealth and a strong sense of patriotism.

On the fifth day, tribal contests took place which were strictly limited to participation by Athenians from Attica’s ten tribes only. Events included euandria (a contest of strength, beauty and physical excellence), Pyrrhic dancing (martial dances performed in armour and accompanied by an aulos) and boat races (the most prominent being held in nearby Piraeus). Such events were intended to emanate and create a sense of tribal pride and unity.

The evening before the festival procession took place, a two-mile torch race from the Dipylon Gate to the Altar on the Acropolis occurred followed by an all-night celebration. The winner of this race was granted the tremendous honour of lighting the sacrificial flame for Athena’s sacrificial ceremony the next day.

On day six, the great procession and main sacrifice took place. The famous Panathenaic procession (Pompe) depicted on the Parthenon’s frieze went from the Dipylon Gate through the Agora and to the Acropolis. The participants included a wide range of priests, magistrates, musicians, elders, cavalry and citizens. The procession was designed to accommodate a giant wheeled ship carrying a newly woven peplos which would be taken to the Acropolis and offered to the ancient Cult Statue of Athena Polias. Here, at the altar where only Athenians were permitted one hundred oxen and a number of other animals were sacrificed in what was known as a hecatomb. Athena was given her share, then her priestesses, followed by the most senior Athenians in attendance and finally, the resulting meat was shared in a communal feast amongst citizens. These events marked the climax of the Great Panathenaia.

On the seventh day, extended additional athletic competitions took place such as apobates and chariot races. Cavalry displays and mock battles may also have been held.

On day 8, further prize distribution and celebration occurred. Prizes such as crowns and amphorae of olive oil were distributed amongst the winners of various competitions. Such winners were recognised and granted civic honours; dancing, feasting and public revelry ensued. The festival concluded in a symbolic showing of unification and Athenian honour.

The City Dionysia was a festival with origins dating back to the 6th century BC which was held every year in honour of Dionysus, God of wine, fertility and theatre. The festival came about because of an alliance forged between Athens and Eleutherae. As a token of friendship and unity, the Eleutherae gifted the Athenians a statue of Dionysus. The Athenians declined to accept the gift because of a general feeling of disconnect and suspicion towards Dionysus felt by the people. Following these events, a plague ravaged the genitals of Athenian men, leaving them infertile and diseased. Fearing that their refusal of the statue resulted in the plague (a divine punishment by Dionysus), the Athenians reversed their decision, accepted the statue and established the City Dionysia, a festival dedicated to Dionysus. With these actions, the plague ceased and the male population who had been affected regained their fertility and were relieved of their sores.

*a historical reconstruction of the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, 6th century BC

The City Dionysia served as a celebration of drama, civic pride and religious dedication. Moreover, it was a significant platform for the first showings of dramatic and comedic works by playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes, Greek titans of drama. The festival took place during Elaphebolion (March-April) and had a duration of roughly 5 days. Its being held early on in Spring symbolised renovation and fecundity, a sense of continuation and promise.

It was the case that the majority of the City Dionysia was held at the Sanctuary of Dionysus, on the South side of the Acropolis. The sanctuary encompassed a sacred temple and altar as well as a sizeable theatre in which there stood an altar to Dionysus located in advance of the stage. The process of choosing the plays which were to be performed here was superintended by an elected official, the eponymous archon. This administrative figure was charged with selecting 8 playwrights (3 tragic, 5 comic) who authored a total of 17 plays all of which were performed over the course of the festival. Another of the eponymous archon’s duties was to choose a choregos, a civic role adopted by a citizen wealthy enough to either finance the performances or pay for a trireme; the choice was his but once selected he was obligated to perform this liturgy. Those who participated in the plays financed by the choregos included one hundred constituents of individual Attic tribes who took part in the dithyramb and other professional and amateur actors who performed the works written by the playwrights and who comprised the chorus, a singing and dancing company.

On Proagon day, a number of days before the official start of the festival, a ceremony was held where playwrights were initiated and provided with summaries of their works. Alongside the playwrights, choregoi and actors were introduced, events which built up a sense of anticipation and fostered excitement before the festival began. During this preliminary stage, civic awards were presented and fallen citizens were honoured.

The night before the Dionysia began, a torchlight procession took place, an event which sought to reanimate and recall the day on which the statue of Dionysus was brought into the city.

On day one of the festival the opulent Pompe (the procession) made its way through Athens to the Temple of Dionysus. The Pompe comprised citizens, choregoi, dancers, metics and young girls carrying ritual baskets. In a nod to themes of fertility central to Dionysus, Phallic symbols were carried by members of the procession in his honour. Sacrifices of bulls and other animals would have also taken place during this time. Following this, dithyrambic competitions between members of Attic’s ten tribes took place; each tribe would enter a chorus of men and boys to compete in the Theatre of Dionysus. To conclude the festival’s opening day, Komos ensued; a nighttime, rowdy, drunken revelry with drinking, singing and dancing amongst men in public spaces.

On the second day, the festival’s opening ceremony and opening rituals were performed. The opening ceremony included a piglet sacrifice carried out by the Priest of Dionysus and a libation to the gods poured by each of Athen’s ten generals. Rituals involved the parading of tribute payments between allied states and territories and the presentation of armour to sons of fallen soldiers’ courtesy of the state, both events which emanate vehemently a sense of civic honour and political exhibition. Day two also saw the initial five comedies performed; a cost of two obols was required to attend performances of works composed by playwrights such as Aristophanes, cleverly designed to mock public figures, reflect on public life and most importantly, to entertain.

Day three marked the first of three days exclusive to the performance of tragic trilogies. An individual playwright set forth a trio of tragedies each conveying the complexities of human struggle and pain and raised meaty philosophical questions regarding existence and endeavour. These were followed by a single satyr play from the playwright, providing the audience with comic relief. Examples of these works include Aeschylus’ ‘Oresteia’ and Sophocles’ ‘Oedipus’ trilogy.

Both the fourth and fifth day followed the same format as day three; on each a fresh tragic playwright presented his trilogy and satyr play which conveyed similar themes of religion, justice, fate and war. Subsequent to this, once all plays had been performed, post festival, the judging began. This process involved ten randomly selected judges, one from each of Attic’s tribes, taken from a pre-chosen group, individually ranking the plays and placing their selection in an urn. The eponymous archon would then choose five of the ten lists and calculate the most votes cast for any given play. The winner of the voting process was awarded a garland of ivy. In addition, the choregos of the victorious playwright was given the honour of funding the production of a monument featuring his and the actors, musicians and eponymous archon’s name on it, celebrating their collective triumph.

The importance of the altar in ancient Greek and Roman festivals

The altar’s role within ancient Greek and Roman festivals was a sacred and central one. Altars served as structures of symbolic significance, emphasizing the connection between humans and gods.

*Greek marble altar, late 2nd or early 1st century BC

In both Greek and Roman festivals, the altar was the place at which animal sacrifices, libations and offerings to the gods would take place. As such, altars were crucial for the proper worship and completion of the majority of religious ceremony which occurred at festivals. In the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, sacrifice was seen to be the primary act which demarcated religious observance; an act which took place at the altar.

Furthermore, altars were sites where divine beings might be communicated with; offerings were given as a transactional practice, ensuring the gods received their due and that spiritual harmony was preserved between the human and the divine. The constant passage of blood, smoke and flesh to the heavens conveyed vehement physical and emotional intent and sentiment toward the deific beings the people believed sustained them.

*Altar of Mars and Venus, dedicated in 124 AD

Many ancient festivals centred their processions and public rites around altars, usually outside, where large groups of people would gather to participate in events of civil unification and worship. These communal gatherings reaffirmed notions of collective identity and were where loyalty was shown toward the state and its leader.

In conclusion, the altar’s place within Greek and Roman festivals was as a key religious device, constituting the area where humans and gods connected. It was requisite for the performance of festivals, ritual purity and community identity. Therefore, its importance and significance for the performance of divine celebrations within ancient Greek and Roman festivals cannot be overstated nor can its symbolic status be underemphasized.

Why people attended ancient Greek and Roman festivals

Ancient Greek and Roman festivals were spiritual in a deep and profound fashion. People who participated in the honouring of the gods were provided a vehement sense of moral purpose and divine favour, a feeling of being protected from the hard forces of life by the gods they worshipped. Therefore, religious rituals such as sacrifices and processions gave people an opportunity to seek divine connection and assure the blessings of the gods.

*’The Entry of King Otto of Athens in Greece’ by Peter von Hess, 1839 AD

In addition to this, festivals included events which provided tremendous entertainment and awe-inspiring spectacle to those attending them. Athletic competitions, music, drama, chariot races and gladiatorial games were all on show at festivals in ancient Greece and Rome. In Greece, festivals such as the City Dionysia were abundant in performances of fresh Greek tragedies and comedies. In Rome, people enjoyed the mock naval battles and gladiator contests of the Ludi Romani; events which were free to the public and delivered high quality entertainment and excitement on a fairly regular basis to the people who attended them.

Moreover, everyone participated in festivals, they were communal and could be attended by citizens regardless of status or rank. This stimulated and fostered the establishment of new relationships between people. Festivals served as scaffolding upon which the establishment of new families and friendships might be constructed. Civic identity was celebrated and shared values reinforced, notions of belonging to a larger group of people were prominent in people’s minds.

Additionally, public feasts were held at festivals where meat from sacrificed animals was cooked and distributed amongst those attending, including the poorer classes for whom the consumption of nutritious food such as meat was not a regular facet of their diets. Pleasures such as relaxation and free, nutritious food were necessary for people living in societies whose lives were often very labour-intensive and whose daily life was a struggle. Festivals took place during public holidays, periods during which business and legal activities were suspended, offering citizens a break from work and all of the other struggles people living in the ancient world had to contend with.

*from the Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus depicting the Census frieze, late 2nd century BC

For those looking to rise in prominence, especially young men, festivals provided an opportunity to gain prestige and honour through competitions and performances. Talented young athletes, artists, orators and poets exhibited their ability in the hope of acquiring fame or even patronage.

Furthermore, festivals played a key role in preserving and perpetuating history, myth and stories through the retelling those of cultural and artistic significance. Customs and rituals passed down over generations were preserved by fresh engagement and participation which took place at festivals, mitigating the risk of ancient tradition fading away whilst fortifying feelings of cultural identity.

In conclusion, the people who attended ancient Greek and Roman festivals enjoyed and cherished them because they combined celebration (both religious and cultural), entertainment and social endeavour into a single package which provided opportunities for occasions of emotional and spiritual pride and nourishment, symbolising the unification of a cities’ population under shared myths, gods, and traditions.

The importance of festivals for honouring the gods

In ancient Greek and Roman culture, festivals served as a medium through which people could show appreciation and loyalty to the gods, entreating them for both domestic, personal success (such as a good harvest) and for the prosperity of the state in war and other wider matters. As such, sacrifices, prayers, processions and offerings were all acts which people believed would maintain the gods’ favour and protect them against the many forms of divine retribution.

The Centauromachy and the Amazonomachy

The Centauromachy and the Amazonomachy were both mythical battles in ancient Greek mythology which represent the struggle between ruthless barbarism and progressive civilization.

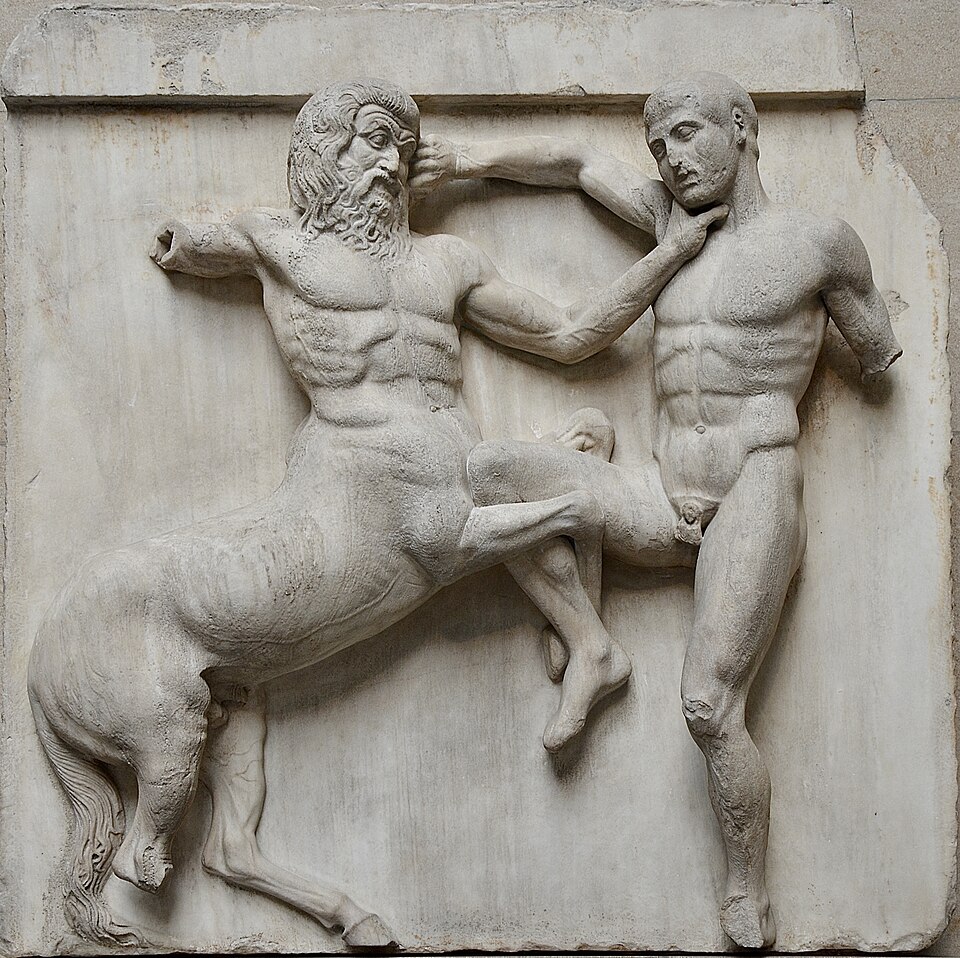

The Centauromachy was a battle fought between the Centaurs and the Lapiths. It came about as a result of the Centaurs being invited to the Lapith King, Pirithous and his bride, Hippodamia’s wedding feast. Originally, they came as friends of the King, however toward the end of the ceremony, they became feverishly drunk, affecting them to abduct female attendees, amongst them the bride. Conflict ensued. A notable guest at the ceremony who took part in the clash was none other than the mighty Greek hero Theseus, a great friend of Pirithous. His efforts to rescue Hippodamia from the Centaur Eurytion were altogether successful and marked the first of many fights Theseus had with Centaurs who he killed during the battle. It is fair to say that without the help of Theseus, the Lapiths may not have emerged victorious from the battle that day. Nevertheless, it was an affair which would later stand to symbolize the struggle between the Centaurs, a species who represent all forms of ferocious, untamed nature and the Lapiths, who represent a Greek mode of reason and soundness of mind and spirit. The battle is often depicted in temple structures, perhaps the most notable being the Parthenon metopes in Athens.

*a marble metope from the Parthenon, 445-440 BC

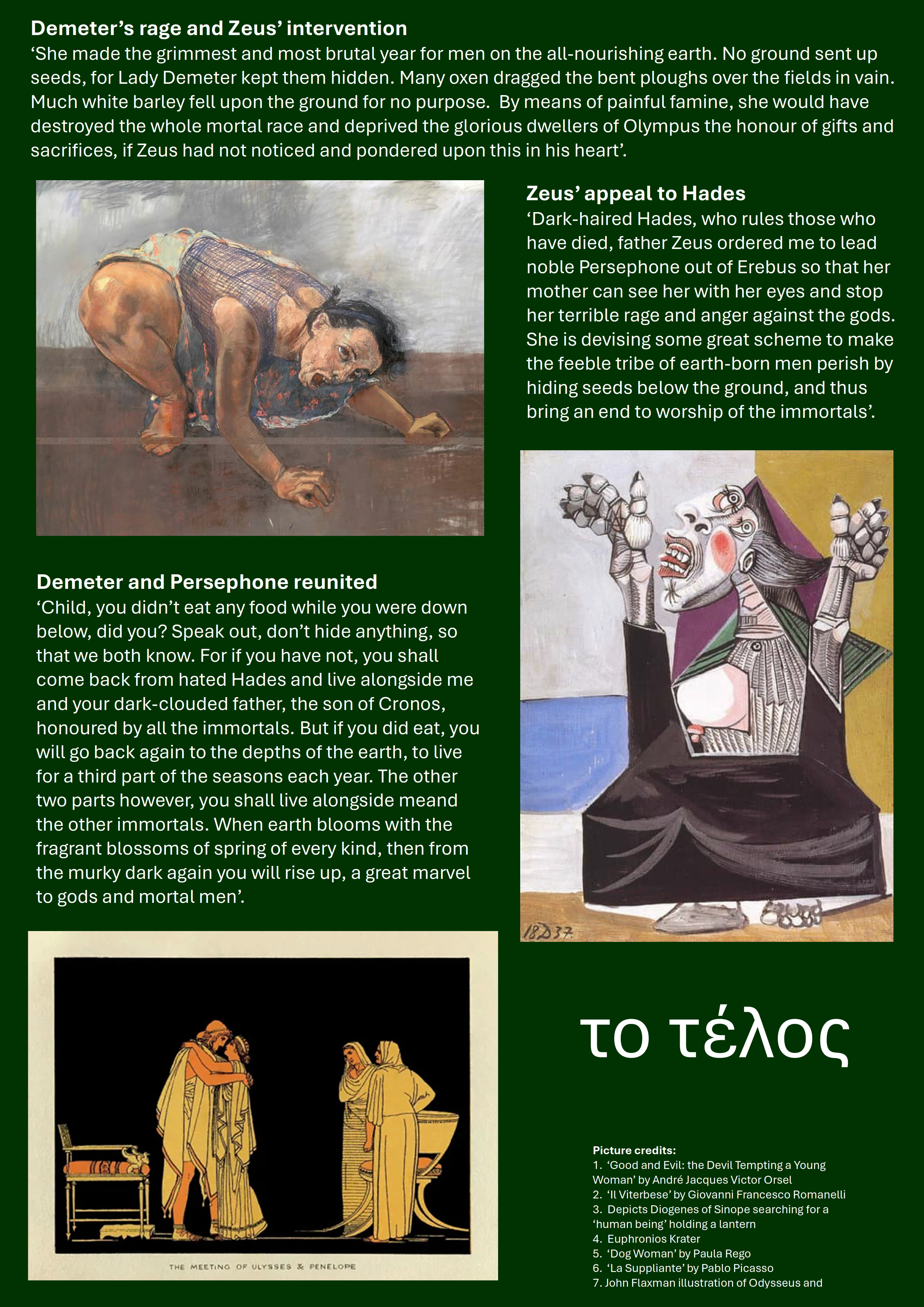

The Amazonomachy was a battle fought between the Amazons, a prominent tribe of female warriors and the Greeks. It came about as a result of Herakles’ ninth labour in which King Eurystheus sent Herakles to obtain the belt of Hippolyte, Queen of the Amazons. The belt was a gift from Ares and was highly prized by the Queen. When Hippolyte heard that Herakles was in pursuit of the belt, she offered to grant him it peacefully. However, before Herakles was able to get word of this, the goddess Hera (who despised Herakles beyond measure) spread a rumour amongst the Amazons, saying that Herakles was planning to abduct their queen. Therefore, the Amazons waged war against Herakles and his men, a battle which would become known as the Amazonomachy.

Another version involves Theseus and tells of how the king of Athens abducted Antiope, an Amazon queen. In some stories, he accompanied Herakles on his journey and took Antiope as a trophy. In others, the queen fell in love with him and subsequently went to Athens by her own free will. Either way, the Amazons viewed the actions as a severe affront and invaded Athens to get Antiope back. Having crossed into Attica, a vicious conflict ensued which would become known as the Amazonomachy. The battle took place near the Areopagus and ended in victory for Theseus and his men over the Amazons. It is the case that Antiope died in all versions, whether fighting with Theseus or against him she was killed either by mistake or by another ferocious Amazon warrior.

*a marble slab from the Amazon Frieze of the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos, 350 BC

Depictions of the story can be seen in numerous works of Athenian art, most notably on the Parthenon metopes.

On whether the Greeks or the Romans expressed their power better in their architecture

The Greek and Roman civilizations were both, in their prime, amongst the most prominent and powerful societies the world has ever seen, pioneers in technological advancement, cultural and religious expression, artistic progression and architecture. Moreover, both the Greeks and later the Romans were responsible for some of the finest and most magnificent structures ever conceived. These structures served a variety of different functions and were created to fulfil a wide range of ideological purposes, usually expressions of religious devotion, artistic and architectural endeavour and most importantly, as a way of expressing the power each had achieved, symbols of domination, progression and might. It is the case that designs and constructions which were built to achieve these goals are amongst those with the most staying power, survivors amidst the demise of their makers, buildings whose magnificence we marvel at to this day. Moreover, it is important to remember that without Greek architecture and engineering, many of the most spectacular examples of Roman architecture and engineering would simply not exist. Such was the influence ancient Greece had on Rome during its inception until its eventual collapse. Therefore, it is crucial when examining and contrasting examples from Greece and Rome to bear this fact in mind; that because so much of Rome and Roman ideals and thought was derived from the Greeks, their creations should not be considered altogether separate.

*a column from the Ionic order of Classical architecture, from the Erechtheion temple, 421-405 BC

The Parthenon. When one thinks of ancient Greek architectural examples it is the surely the one that springs most readily to mind. Built atop the Acropolis in the centre of Athens during the height of the Athenian Golden Age in mid-fifth century BCE under Perikles’ rule, the Parthenon is a temple dedicated to Athena Parthenos, Athens’ patron god and divine protector. Having been designed and engineered by Iktinos and Kallikrates with sculptural direction by Phidias (responsible for the massive internal cult statue of Athena), the Parthenon was primarily doric in style with a number of ionic elements and constructed mostly from Pentelic marble hauled from the Mount Pentelicus quarries near Athens. The Parthenon features eight columns on each of its shorter ends (east and west) with seventeen along each of its longer sides (north and south). Examples of the designers’ attention to detail in attempts to achieve visual perfection, the Parthenon’s stylobate has a slight upward curvature and columns which are subtly swelled, bulging which produces a convex curvature of their shafts. The interior of the Parthenon is divided into two main sections: the Cella or Naos (housing the cult statue of Athena) and the Treasury or Opisthodomos. The Parthenon’s exterior decoration consists of metopes which depict mythical battles such as the Amazonomachy and Centauromachy, both symbolic of Greek triumph in battle, emphasizing power in conflict. The Panathenaic procession is depicted on the continuous ionic frieze, an event which represents civic-religious unity and collaboration. Large triangular structures known as Pediments on the eastern and western side of the Parthenon depicted Athena’s birth and the contest between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of Athens, both events central to Athenians’ cultural identity.

*The Parthenon atop the Acropolis in Athens, 447-432 BC

The Parthenon was constructed during a period of tumult within Athens. Following the sack by the Persians in 480BC, the Acropolis had been brought to ruin and many of its temples destroyed, burnt to the ground. However, by the mid fifth century Athens, following the establishment of the Delian League, had risen to prominence amongst Greek city-states and emerged as a powerful leader in control of the alliance. Following the Persian wars, in 447BCE, Perikles, an Athenian general and statesman, initiated a building program to rebuild Athens using tribute money collected from city-state members of the Delian League. The money was transferred from the League’s treasury on Delos to the Parthenon where it was stored in the treasury, the funds used to glorify Athens, marking the beginning of a period during which the Athenian state was at its cultural and political zenith. As such, the Parthenon was constructed at a time when Athens was looking to rise in power, wealth and prominence following the end of the Persian wars. Its construction marked the beginning of an era during which Athens was a city at the height of its power and at the forefront of art, philosophy and architecture. This is reflected heavily in many of its architectural and design features, from the depiction of Greek victory in conflict on the metopes to the celebration of civic-religious unity on the frieze, the Parthenon’s attempt to display and symbolize power was palpable.

The Pantheon was originally constructed in the Campus Martius area of the city of Rome in 27BCE by commission of Marcus Agrippa under Augustus’ rule. It was later rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian around 120CE. The building bears Agrippa’s name on its face with an inscription which reads: ‘M AGRIPPA L F COS TERTIVM FECIT’ (‘Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, built this’). The Pantheon was a temple designed by the architect Apollodorus of Damascus with contributed design from Hadrian. Its front (portico) was clearly constructed with heavy Greek influence whilst the rotunda and dome are a perfect example of the innovations the Romans made in engineering at the time. The Pantheon was built using a mixture of materials including granite, marble, brick-faced concrete and Roman concrete. The portico was of Classical Greek design featuring sixteen Corinthian columns, the rotunda was a very large circular interior space and the dome which sits atop the rotunda was revelatory in its design and construction and massive in size and complexity. It remains to this day the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever created. It is 142 feet in diameter and the same in height, forming a sphere of perfect proportion when viewed from within. At its pinnacle is a nine-metre-wide circular opening known as an oculus which allows for the only source of natural light in the building, a reference to the heavens. The Pantheon’s ceiling is coffered, light, functional and ornamental. The floor is of slightly convex design to allow water to drain from the oculus.

*The Pantheon in Rome, commissioned 27 BC, completed 126-128 AD

The Pantheon was constructed during a time when the Roman empire held the most territory in its history, a time of relative tranquillity and affluence for those in Rome. Hadrian, the emperor at the time, was renowned for his passion for architecture, a patron whose structures were profoundly influenced by Greek ideas. Because the Pantheon buildings had burned down, Hadrian viewed the project not simply just as a restoration but as root-and-branch innovation, particularly given the complex and radical nature of the use of concrete and engineering featured. The Pantheon, unlike the Parthenon, was created to honour all Roman gods, not a single one, as suggested by its name; “Pantheon” is derived from the Greek pan (all) and theos (gods). As a structure erected under imperial rule, the Pantheon was a space dedicated to the unification of all gods under the imperial banner. Furthermore, the use of diverse materials and the complex mathematics which contributed to the build were designed to strike awe and astound all those who saw it, and make people view it not only as a building but as a symbol of technological prowess, philosophical advancement and political and state power. As such, the Pantheon is a demonstration by the state that the power Rome had come to wield was as a result and was altogether reliant upon divine consent and a mutually beneficial relationship with the gods. This further implies that both Agrippa, Augustus and later Hadrian were leaders who wished to construct monuments which connected them to the gods and portray each as somebody, who in the eyes of the people, was intent on preserving religious order. And of course, as men who had the initiative and power to enact the design and build of one of the most revolutionary structures in the history of the world. This, in itself, is a demonstration of power through architecture.